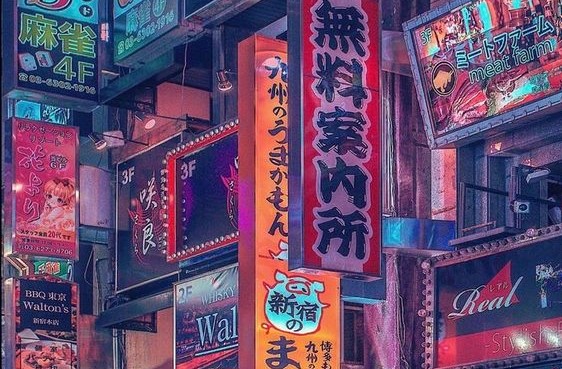

The first time I leave, I’m nineteen and my mom is crying in the airport. I laugh instead of hugging her and make her stand in front of a sign that reads “Trauma Kit” while I take a picture, hoping it will diffuse the tension because I’m not sure I can parallel her sadness.

She’s been blocking my trip to study abroad at Oxford University for months, refusing to talk to me about it even though it’s only three weeks in July. Her reaction sedates my excitement—I want her to be happy for me, but she’s not, so I have to hope I’ve made the right choice alone.

She doesn’t let me say goodbye, her always rosacea-red cheeks blooming a deeper, almost bruised brown, a signal of more tears to come. She pushes me to the security line, bubbling eyes cast down, mumbling that I’m only making it worse by standing there.

I try to make her laugh by running through the TSA gates with my arms spread out, dipping back and forth between empty rows, no one in the way to crowd it. When I turn around to see if it worked, she’s not looking, her face pressed deep into my dad’s golf shirt. He shakes his head and waves a large hand, an open mouth grin taking up his face. I turn back towards security, resuming my carefully curated not-weird composure, locked legs and trying to stand straight with the weight of my carry-on backpack threatening to tip me over.

When I get back from England three weeks later, she’s sullen. “Papa always said the middle child leaves first, and I didn’t believe him,” she says. “You promised you wouldn’t leave me, you can’t leave me with them.”

I pull at the fringe of my shorts, think about my two sisters, parted by four tumultuous years without me in the middle to bridge them. “They didn’t kill each other while I was gone though. I think you’ll survive.”

When I was a kid, my parents used to listen to cassette tapes on car rides. The cassettes were by some psychologist who believed in the importance of birth orders. On one of the rare days my parents went out without us, my mom came home and stood under the stovetop light, dishing out our destinies. She said the middle child is a negotiator, perfect for jobs like president or ambassador because with all the practice of bringing siblings together what more work could bridging nations be. The psychologist said the middle child usually leaves first, but she didn’t believe it. I was always her favorite, something she tells everyone, especially my sisters, like it will kick them into competition.

I’d talked about leaving but I’d never done it before, now this short trip away had begun to prove her wrong.

“You like Boo better anyway, you won’t even notice I’m gone,” I say.

“But you’re the glue that holds the family together,” she says. “You can’t leave me. I made you.”

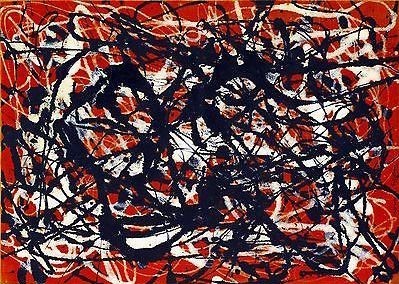

It’s a weight I carry with me always. The expectation of moderating, silencing, connecting. If my family were each a telephone line, I’m the operator. I don’t take my own calls, I’m only expected to choose who to connect to the other.

My mom and I don’t fight about much, but we do fight about homeschooling. I’ve always wanted to pick the homeschooling apart, analyze every choice my mother made. But most times I can’t because I haven’t found anyone who understands it even a little and I feel like I’m the one who’s wrong when I say that any part of it didn’t work like it was supposed to. My two sisters don’t feel the same way I do, at least not strongly. They tilt their heads, agree lightly, and counter with uncertain disagreements. I can’t criticize homeschooling with those who didn’t experience it unless I want to condemn the entire system. I become a spokesperson for the entire methodology even when I don’t want to.

“You should be grateful,” Mum says. “I made you, you’re mine.”

Somehow the homeschooling is ownership, a shackle around my ankle when at best education should be a type of freedom. Most people are indebted to a faceless mass of strangers who were paid to teach them for twelve years but were never possessive of their work. I can never part from the person who made me—leaving is ungrateful and so I know that I cannot leave without also spitting in her face.

Mum always wanted to protect me from the world, from public school, from the public, at least that’s what she says.

“You don’t understand the pressure of high school. Do you even understand how awful it is when you don’t have the right clothes? Or a boyfriend? Or your hair doesn’t curl right?” Her eyes bug out, disbelief at my entitlement. But I think that this is a façade erected to maintain the homeschooling tradition, like she’s trying to say there is something wrong with the world and only I can protect you from it.

But I am expected to say no. No, I don’t understand. Thank you, I’m glad I didn’t have to deal with any of that pressure.

“You’ll never understand the pressure of needing to fit in,” she says, “and I’m jealous of you.”

I smile bleakly and nod, agree listlessly. I don’t know how to explain to her that by wishing to remove us from the pressure, she created it. How can I explain to her that the thing she wanted to protect me from had been in the house all along?

My sisters don’t talk about leaving, not quite like I do. When I say I plan to leave Massachusetts and never come back, my older sister calls me a traitor. She scoffs and looks away, answers to another person like I’m not worth talking to if I can’t be realistic.

“Yeah, she’s definitely going to marry some guy and have like, seven kids,” she says, dishing up a future she is determined I have.

Mum agrees, looking at me with sympathy. “I didn’t want kids either,” she says. Her lips curl into a Lucille Ball worthy cringe. “I thought they were gross. I still think they’re gross. But it’s just what you do.”

“She’s gonna homeschool a bunch of kids, and live here forever, and be a secretary,” my sister says, her barely controlled anger wafts around the dusty frames and my great-grandmother’s refurbished couch, swaths of fluff hanging from where the cats have dug in. “Just like her mother.”

Mum winces faux-dramatically, cooing a soft “ooh.”

“Most likely,” I say. No matter of convincing without action will change their minds. For now, the twenty-year-old expectations of secretary turned depressed housewife looks fulfillable. I haven’t done much to combat this expectation anyway.

For my sisters, the close quarters were a warm fuzzy hug, a weighted comforter during a long winter, a security. The repetition, the tradition, the weeks spent always doing everything just the same satisfied my older sister and her obsession with control and order. It was perfect for my younger sister, a self-proclaimed sloth not wanting anything to challenge or change her; she’s been playing the same video game over and over since she was nine. During holidays, while I begged for us to find a new tradition, they dutifully turned the ‘90s stereo to Christmas music and started sorting the branches of the decrepit plastic tree, so filled with mold that my eyes stung and my lungs burned. A break from tradition is a break from family, and so when my older sister calls me a traitor, I know she is right.

I feel like a traitor most days when I leave the house and do things Mum would have condemned me for before. Things like using elevators, opening doors with my hands instead of my elbows, or talking to people. Even though she doesn’t have to know, I feel her voice telling me to not eat out of salad bars or reminding me to flip off the school bus when I drive by, to stop loitering and to come home. As much as I want to break from the homeschooling, I don’t think I ever will be able to without breaking from her.

I was raised on a steady diet of contradiction, constantly digesting when Mum thought the rest of society was valid and when it wasn’t. Whether she meant to or not, Mum acted like she believed she was better than everyone else and she didn’t want us to assimilate to the perceived idiocy of society. She attacked them subtly everywhere we went, mostly in our sudden and short-lived desires to become them—the kids at the ice-skating rink were prissy, the kids at the swim team were gawky jocks, the other homeschoolers were weird homeschoolers, college was made for idiots. When we carefully became a part of these places, we were the normal homeschoolers, the good swimmers, or the smart college students, while everyone else kept their preassigned label. It didn’t feel right, like we were bad by association and she was only too nice to tell us.

It was always us against them; everything that wasn’t her was wrong. Her opinions were the only influence I had soaking into my pores until I wasn’t sure where she ended and I started.

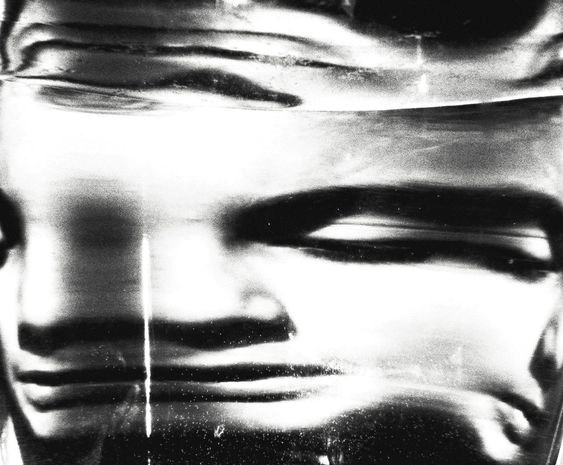

I never really figured it out. Now when I hear myself telling someone I don’t like cartoons, I wonder if it’s because I don’t or because Mum hated them so much that I adopted it, just figured that’s who I was going to be because she was really the only person that I knew, so how was I supposed to know any different. I became an extension of her, a little tendril of manipulated interest sent out after sixteen years of cultivation—I can never really shake the feeling of being an outsider.

When I do contradict her, like when I find myself out among them, I feel the betrayal eating at my stomach lining like it’s trying to get out. I’m conflicted between wanting so desperately to be like them but I still see it through her eyes, and I can’t figure out who I’m supposed to be if it’s not her.

I told her once that I felt like an anthropologist most days. Like I’m immersing myself in a new culture but never actually becoming a part of it, distancing myself just enough so that I’m still an observer, able to understand the quirks, the flaws, the oddities of it without getting invested. She said that I was being ridiculous, she never did that. She never made me like that, at least not on purpose.

I was never very good with people, a trait I like to blame on homeschooling but know that it’s most likely due to an abrasive personality I’m not willing to shake. I learned this not too long after I became friends with another homeschooler who I thought should’ve been compatible, but even he didn’t stick. I couldn’t blame his departure on the idea he thought I was a weird homeschooler, so I had to revel in the fact that I must be plain weird.

After friendship didn’t work out, I decided to try dating. One of my ex-boyfriends was the first person I’d ever met that hadn’t really cared that I was homeschooled, catching me off-guard because at least two of my other dates had only been interested in the fact I was homeschooled. While his lack of interest should have made me feel less like a trophy, it made me uncomfortable; anticipation like a brick in my ribcage waiting for him to react like I was used to so I could expel the weight. I talked about it all the time, more than I ever had with anyone else, like I was trying to drive a reaction out of him.

The car curved gently around the bend and I glanced at the Big Blue Bug along the highway, an advertisement for an extermination business that marks the strip between Rhode Island and home. I admired the darkening blue sky behind it, only half listening to my then-boyfriend tell me for what I imagined to be the ten-thousandth time how his graduating class was only thirty-two people deep. The pride of his achievement, of being one of a few, puddled thick on the steering wheel and all I could think about was my mom and how similar his thinking was to hers, that being unique was all numbers and something that mattered.

Since I like to pick at scabs, I said, “Well mine was only three. Technically one.”

I watched him nod thoughtfully out of the corner of my eye. I tried to focus on the highway, phantom braking every time he nearly slid into another car. I did it quietly to avoid his gentle condescending, “Relax, chica,” every time my seatbelt locked.

“I would have been good homeschooled,” he said.

I tensed reflexively and scoffed. “What?” I said.

“Like, I wish I had been homeschooled,” he repeated. “I think I really have the personality for it. I hated the pressure of high school. I’m jealous of you.”

I scrunched up my nose. “I mean, it wasn’t all like that,” I said, stuttering over words, defensiveness spilling in. “I think that’s a weird thing to say.”

He ignored or didn’t notice my annoyance and continued to say he would have been smarter, more driven, more dedicated to what he wanted to do. How he wished he had been homeschooled because then he could have done anything he wanted. He accounted for my lack of friends in his own fantasy, remarking how he would have been better without friends, that he didn’t need people even though he had a huge group of friends and still complained about being lonely when I didn’t text him back.

“It would have been so good,” he said, hitting the steering wheel with his palm. I didn’t answer, instead watching the dark concrete bridges we passed under.

I don’t know how to explain what homeschooling really was like. It wasn’t field trips to the Boston Museum of Science (and even when we went, Mum told us not to touch anything) or hours of indulgence into hobbies and interests, trips to the library. How do I explain the years spent staring at the ceiling, the cold sunshine dragging itself through the window, not bothering to move because there was nothing to do anyway. How I decorated all my walls with photos so at least I would have something to look at. The internet was turned off, the piano was too loud, the TV didn’t work, and I’d read all my books. How do I explain the boredom, to live without sound or action because the only people I had were the walls and my parents, and sometimes they acted the same. How could I explain the itchiness that went far beyond the surface, manifesting in organs I couldn’t scratch even when I tried to dig deep.

So I didn’t. He never asked me anyway, so I let him talk and talk about how good I must have had it until he tired himself out. Then I agreed. Yes. You would have loved it. I’m sorry.

My desire for friends was an obsession from the start, an absurd one I tried to measure at every turn. I tried to quantify it, nail it down to mathematics because the actual innerworkings of it didn’t make much sense; everyone in my family liked me because they had to, but what made real people want to know me?

Instead of engaging, I counted every text I got from someone, every eye flick, every confused smile or head tilt and I compared them, trying to measure how people’s reactions to me were different to others. While my sisters drifted ahead of me in measurable contact lists and birthday gifts, I lagged behind trying to count the amount of times I made somebody laugh.

When I was a kid, I complained to my parents that I wanted friends. They said that I’d have friends when I was in college. It seemed like a long way away, but I accepted that excuse because there wasn’t much else to do. When I neared the end of college and had fewer friends than I had started with, my parents were confused by my inability to socialize.

“You’re such a loser,” Mum says, in language to imply she’s joking but I know she’s not because she talks about it all the time. How she had so many friends in her twenties, how she just can’t understand why I don’t have any. Her only surviving blond pieces curl tightly in ringlets around her oval face, and she’s jumping into skinny jeans, a date night with her old high school friends on a Friday night the only time worthy of dressing up. “You’re wasting your twenties. You wouldn’t believe what I’d done by the time I was twenty.”

I want to tell her that I understand the life she had, that I thought I would have that life as well. But they all still feel so foreign, like I don’t fit so it’s easier not to pretend to. I can’t demand a place in a world that I’m still not sure I belong to.

Despite her nagging, Mum doesn’t like when I have friends, or when I have to leave the house. She can’t do anything to stop me, she doesn’t impose any rules, but she says how much it hurts her for me to not be home, that she can’t lie to me—she has to be honest. When I’m out I can feel her sadness eating at my nailbeds like a reminder to go home.

My mom homeschooled us, kept us at home because she wanted friends, and by her design I can now be nothing but her friend. Sometimes I don’t tell her my work schedule, instead I leave in uniform and wait for her to text asking when I’ll be home because she misses me. If I tell her I’m working a nine hour shift beforehand, she yells that I need to quit my job because I hate it anyway.

She follows me out to the garage, holding her thinning robe together while I tie up my old sneakers. “Remember your poor old mum, all alone, by herself,” she says as I squeeze out past her car towards mine parked in the driveway.

I tell her I never think of her when she’s not there, like she ceases to exist if I don’t see her. But most times I see her in everything, a cold hand clenching my wrist in a gesture supposedly of love.

When I got my first job at sixteen, I found the world exciting, like touching things I wasn’t supposed to was rebellion. I liked driving, not responding to texts, working, talking. I was the annoying cashier that nobody wanted to bag for, the one who asked too many questions in between customers and only worked nightshifts so I could work with other teenagers. I was making up for lost time, swallowing everyone whole.

Despite my sudden confidence, there was still a barrier, half the time a physical one. After a few months, I began working behind the customer service desk, looking out over the rows of cashiers. I think I burned myself out; I reverted to my old self, a shivering kid in a pool, staring at everyone as they swam away from me, stuck to only listening, and watching, and counting.

I grew up thinking I’d be able to shake the homeschooling, like I was some butterfly that, at eighteen, would magically shed itself from its origins, never needing to look back. It took me longer to realize that I wasn’t ever going to be able to shake it because the homeschooling wasn’t only education, it’s my family, all of them and they’re all I have. I learned everything through my mom’s filter and whether that’s good or bad, I’m not sure. Perhaps everyone has filters, only more spread out than mine so they are influenced by dozens of people, not one.

I am so desperate to complete the homeschooling narrative, to escape from the people that made me. To yell from a balcony that I am free now, that homeschooling was a jail, but it’s not possible as much as it’s not true. I hate the word escape because there’s no way to escape without implying that homeschooling stifled me, when in most ways it did not.

But I think I am still hoping to escape like other homeschoolers do. I wish I wasn’t. I wish I could be content with the life I have been given, easy like my sisters, hoping for nothing more than an office job and a house down the street. I wish I could cry when I think of leaving, that my home felt like a warm bath, not like a box soft from rain so it’s turning to pulp and I no longer fit, limbs jabbing out at the corners, the lid caving in on my head.

I wish I didn’t have to hurt her, that I could live up to her expectations, but something inside me trembles when I think about returning to the hermitage of my home every summer. My mom was passed self-isolation from the mothers before her and she passed it to me. She lived at home until she was thirty, only leaving when she got married, the last of all my grandmother’s seven children. By homeschooling, my mom tried to recreate the love and comforts of her home, a forever girlhood, mother and two sisters became mother and three daughters—she always said she never wanted a boy. What should have been soft was bruising, crushing us in every time we tried to peek out over the lid, never thinking that we might need a little more room to live than she did.

But I can’t ask her not to love me that much.

When I think about leaving, I imagine going back to where it started, back to where my mom came from. To ditch the dark, cold winters of Massachusetts—the winters of dryness that makes my nose bleed and my eyes burn, the months spent hiding under layers and layers of comforters that never warm me, only bury me. I have to go to the place that my mom says is as hot as an oven but in the dry kind of way, not like here where it’s sluggish and full of bugs and gruff people bent like trees from the weight of the snow. I want to trade for the hot concrete of California, the heat and the palm trees and the stucco and the earthquakes and the fault lines. The women in my family have a habit of running to California when they can’t take it anymore, like it’s far enough out of reach where no one can find them even if they’re looking.

I imagine saying nothing. To leave in the middle of the afternoon in August in my bright yellow beetle, the approaching autumn sun glinting off the windshield. I don’t take anything, the hatchback empty—I’m not sentimental enough to have anything to hold on to.

I don’t imagine her there because I don’t know what I would say to her if she was, but I’m not sure if she would say goodbye to me anyway. But what I know for sure is that I have to go back to where it started, at least, back to California where the freedom came from.