When using poetry as a method of self-defence you need to start with the basics. It’s easier to disarm or incapacitate a potential assailant with form and structure than with content. Not that content can’t have devastating effects – it can. But generally only in expert hands.

The simplest moves in poetic self-defence are to employ a quick couplet or a punchy quatrain. Your low-level hooligan will usually think twice when confronted with ‘The time is not remote when I/ Must by the course of nature die’ or ‘My love is of a birth as rare/ As ‘tis for object strange and high/ It was begotten by despair/ upon impossibility’. This kind of combination allows you to stop feral hoodies bricking your car in the early hours and to focus on the universals of love and death – so killing two birds.

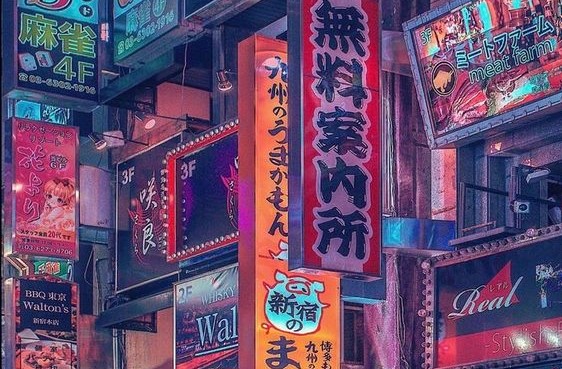

Sometimes, of course, you may find yourself up against a more formidable foe. You’re in a nightclub queue when a group of boozified young men in wrapper-sharp Next shirts gets all puffa-jacketly pugilistic. According to poetic self-defence instructor Gerry ‘The Man’ Hopkins, this is where you need your metric wits about you: “Anapests, dactyls, trochees and iambs are your bread and butter when dealing with more than one assailant. But you want clarity, for the poem’s metre to stand out to someone who, for all you know, is in a cracked-up brain state.” What does Hopkins suggest? “Well, some people think me lacking in aesthetic judgement, but for self-defence purposes The Charge of the Light Brigade is a useful tool. There’s no point trying to use Simon Armitage against a mob. Tennyson makes the stresses stand out, there’s a cultural dissonance and that’s what you want. If your opponents are particularly aggressive – Coleridge, Ancient Mariner – strong iambs and enough variety of line length to keep ‘em guessing.”

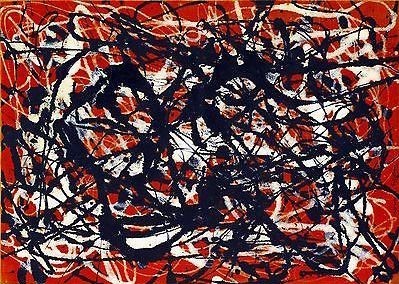

So much for the basics. Other espousers of a quick sonnet or a weighty couplet as a means of stopping people messing with your stuff or getting even anywhere near the entrance of your face, like psychic textual media guru Michael ‘Begin Again’ Finnegan, stress not the importance of stress, but the importance of imagery. “I’m convinced,” claims Finnegan, “that you can only effectively deal with an armed assailant by using imagery.” But is Finnegan really convinced? “Yes, I am,” he says. “There’s no doubt about it – in the right hands, Wordsworth can be a lethal weapon; Keats can kill; Frost is fatal; Marvell is murder. Nine times out of eleven a powerful natural image will force an assailant to consider the cyclical, potentially fecund yet mortal nature of being. This gives you a vital few seconds in which to employ further images, something of a disjuncture, John Clare, say, or Browning. Longfellow even.” A rich arsenal of canonical kit in anyone’s binoculars should you need to de-tool the tooled-up.

But what of content? Sometimes you need your university wits about you when trying to chill the whole f***ing thing down before someone loses some f****ing teeth, yeah? The success of content is going to depend on context, which is why judgement is the hero of the hour. Say you are caught ‘in rigatoni’ with the wife of a local mobster and he gets all De Niro about it, some themes or motifs might really lower the imminent violent explosion factor. You try a couple of lines of Elizabeth Jennings and suddenly the guy’s flashing a piece. Bad judgement. You go for a Larkin stanza and he’s put one in the chamber, man. More bad judgement. In a spot like this, according to Tim Ashanta, Head of Applied Linguistics at the Technological Institute of Applied Technology in Bracknell, “Your thematic choices can either get you killed or see you walking away down a dark and misty moonlit alley with a swagger in your gait and a cool theme tune running while the credits roll.”

What does Ashanta suggest? “You need range, repertoire, and to know the pitfalls.” What are the pitfalls? “They’re the mistakes you could make.” And what are they? “Thematically speaking, they are love and eroticism. Seven times out of nine love and eroticism can get you killed. Literally speaking it’s eight out of thirteen. Ultimately, if there is an ultimate, it’s about subtlety. And range. I once saw a university lecturer foil a gangland topping with only a line of MacNeice and a few images from Songs of Innocence and Experience. Stopped the goons in their tracks. It really does work.” Sho’nuff etc.

Disclaimer: poetry should be used responsibly at all times.