Forty years ago I spent a year in Madrid, in a rented studio apartment on the sixth floor of a narrow brick apartment building on bustling Calle de la Princesa. One room that came fully-furnished with two single beds which we lashed together with twine—thin, tick mattresses on metal frames, like the institutional beds all in a row in the books about the spunky French orphan Madeleine—a round slab of fiberboard atop a stand for a table, two chairs, and a wardrobe. That one room, the echoing stairwell, and our rectangular mailbox in the lobby, beside the concierge’s apartment and the ornate doors onto the busy street, became my world.

After graduating college, my boyfriend, Rick, and I worked and saved for two years to finance this dream. We would write novels, abroad, a glorious word that conjured sophistication and glamour. He also intended to launch a multi-cultural, Spanish/English language literary journal, to be called Artistiberiobras, a made-up word that seemed to demand an accompanying Flamenco hand gesture.

Neither of us had ever written anything publishable. I hadn’t even tried. Yet all of this felt perfectly plausible. We had plotted our futures over endless pots of strong, black tea.

Big dreams. Big plans. To become a critically lauded and massively popular author, only then to return home and impress all the family and friends I believed doubted I would succeed. Impressing them, proving them wrong, was just as important, no, let’s be honest, way more important, than completing a book.

Did I realize how implausible our plan was, what the odds of success were? I must have. Yet I was of an age when I believed daydreams were projections of the future, which they can be, given the requisite luck, hard work and diligence. We left for Spain with enough money to cover rent and expenses for a year, assuming that with the jobs we’d soon find, and the generous advances we anticipated for our books, we could stay as long as we liked, perhaps forever. I’d only cross the Atlantic to meet with my editor and to do whatever it is that best-selling authors do, grant interviews, appear on television and what not.

We bargained for a used Olivetti typewriter at Madrid’s massive outdoor flea market, el Rastro, picked up notebooks and reams of paper, white crockery cups and plates, a matching, stubby-necked teapot, towels, a blanket and a swirling round tablecloth.

Rick became task master and editor. He established writing schedules with daily and weekly quotas for words and pages, which, over time, seemed, at least in my memory, to apply mostly to me. His primary project was the literary magazine, which necessitated many meetings at cafes and bars after which he would return to the apartment to review and edit my daily output, cigarette smoke in his hair, fried tapas and Rioja on his breath.

I can’t recall that I ever ventured out on my own. In time, I imagined myself a prisoner in that tiny apartment, which must have suited the fantasy I’d constructed for myself.

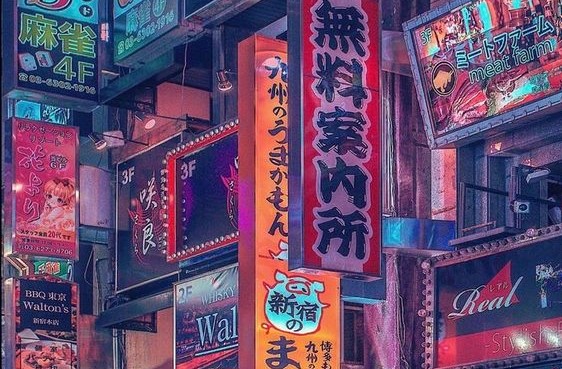

I was 24. This was early 1978, three years after the death of longtime dictator, Generalissimo Francisco Franco. The grand and storied city of Madrid was in the midst of a social revolution. I sensed a fever down on the streets, in the blazing eyes and purposeful step of the throngs who flowed around me as if I were a clunky pebble in a fast-moving stream. The city, a real city, seemed to press at its seams. The narrow cobbled streets pulsed with life. Madrid was as different from Sacramento, California, where we’d been living, as a stale pot of diner coffee is from a fresh, steamy café con leche in a high-ceilinged marble and mahogany café.

The city found me through the one tall window that canted out into the air well that ran through the center of the apartment building. Crisscrossed with laundry lines and windows into other lives, close enough to watch the television across the way, to eavesdrop on a family squabble and inhale their supper. Down to the damp concrete below, where six floors of damp laundry drip, drip, dripped. Open to a square patch of bare sky above.

We drove our neighbor, a cotton-haired widow, crazy with our incessant tapping on the typewriter keys. Bursts of manic typing interspersed with reading out loud to one another, emotive eruptions and pacing the wood-grain patterned linoleum (him) and tears (me) as we edited one another’s work and struggled to articulate our artistic differences. One such heated argument concerned what name I should give my protagonist, a girl who closely resembled an adolescent me. I don’t recall what name I preferred. Rick insisted she be called Gretchen, but couldn’t, or wouldn’t, articulate why. Eventually, I conceded. As our principal typist, he had ultimate control of the final manuscript anyway.

The señora next door seemed ancient to me then, though she might have been about the age I am now. Whenever Rick got really cracking on the typewriter, she would crank up the volume on the TV. The staccato clacking of the keys and the blaring television battled for sonic supremacy on the sixth floor.

Closely attuned to our comings and goings, the moment our neighbor heard us throw the lock on our door, she would stick her head out to wish us good day and to get in a question or two before we, or, more usually Rick, escaped down the stairs. I imagined she feared we were political subversives, generating foreign propaganda behind closed doors. In my fevered imagination, it seemed possible she’d report us to the government.

“We’re writing for American television,” Rick finally told her, since she so clearly adored television.

“Ah, como una telenovela?” she asked, with a hopeful glint in her eyes.

“No, not a soap opera, a detective show,” he said.

“Ah, pues,” she said, with a shrug, as if cop shows weren’t to her personal liking, but were acceptable nonetheless.

After that, we were peppered with questions about characters and plots. We improvised to appease her. I don’t recall the story we spun, yet now imagine it would likely have proven more interesting than what I was working on, a thinly-veiled memoir that professed to make fiction of my rather ordinary life up to that point, set in the San Francisco Bay Area where I grew up.

As evidence that the señora no longer mistrusted our intentions, she sometimes invited us over in the evening to watch a variety show in her cluttered sitting room, sofa and arm chair covered in thick, crinkly plastic, framed photographs of family members who never seemed to visit on the cabinets and walls. We brought her trays of colorful marzipan, shaped like miniature apples, pears and peaches.

On days when I’d exceeded my quota or reached some milestone with the book, my reward was dinner out in one of the dozens of neighborhood restaurants on the side streets off the main thoroughfare. A handful of tables, the set three-course menu posted in the window, red wine from a cask, our own loaf of bread placed on the crisp white paper tablecloth where the waiter also scribbled our order.

Rick was concerned we eat properly, the European way, so as not to be taken for what we were, Americans. He’d schooled me on holding a fork in my left hand, the knife in my right. A feat I barely mastered. And on peeling and consuming the piece of fruit that was generally desert, without touching it with my hands. A skill I never did acquire, no matter how much I practiced.

To conserve our dwindling resources, our more typical dinner fare was a plate of potatoes and onions, sometimes enhanced with a nubbin of flavorful cheese. A thick slice of Manchego with our daily bread was sheer indulgence.

Jobs never materialized, despite leaving resumes anyplace we thought might be interested in an English-speaking employee. The literary journal didn’t take off either. We posted fliers soliciting submissions of artwork, poetry and prose at universities, anywhere we thought young, literary types might congregate. We combed directories at the library and mailed fliers to campuses throughout the Spanish and English-speaking world, spending a small fortune in postage. We received one lonely submission in our mail box. A packet of poems from a young man in Gibraltar.

We might have persisted, but a government official in a fortress-like office building in the city’s center, a Franco holdover, informed us that what we were attempting wasn’t possible. While I didn’t catch the nuances of the conversation—Rick’s Spanish was better than mine—there was no mistaking his stern brow and shaking jowls, the demand to examine our passports, our sense that he might not give them back to us.

Winter was the hardest of all. Our California wardrobes proved inadequate. We huddled around a portable floor heater swaddled in layers, swilling hot tea at the wobbly round table. Rick typed with mittens on, the fingertips snipped off. When we couldn’t stand the chill in the apartment, we sat in cafes and nursed hot drinks. As my novel neared completion, the hours at the typewriter increased. The señora became cross with us. Our invitations to watch the musical variety show ceased. To give her a few hours respite, Rick found an empty, unlocked room at the university where he would sometimes lug the typewriter.

He had spent his junior year of college in Madrid, during the final Franco years. While I had no point of comparison, he assured me the city had changed enormously since then. He deplored the influx of American influences. Fast food franchises, films and music. Massive billboards for the film Saturday Night Fever were seemingly plastered on every available surface. An impossibly slim-hipped John Travolta in a vested white suit, several stories high, one finger stabbing the sky in a defiant disco stance.

Newspaper and magazine kiosks were on every corner, like Starbucks are today. Clutches of men huddled within the kiosks’ orbit, drawn by glossy cover photographs of naked girls. Older women, often clad in head-to-toe black, hurried past with their rolling shopping carts, censorious eyes on the pavement. Headlines proclaimed the “Sexy Boom.” Rick expressed professional curiosity about the proliferation of titillating journalism. He said he sensed an opportunity. We bought a few magazines from one of the kiosks and studied them back in the privacy of our apartment.

There’s one girl I still remember. She had a centerfold, complete with an informative, if abbreviated, interview. Her professed name was Gatita and she liked cats, of course, but also fuzzy sweaters and curling up by the fire with a good book. In her photo, she wore nothing but girlish white bobby socks rimmed with lace.

Without jobs, and to bridge the gap before our books found publishers, we needed an interim source of income. We decided to write short stories. Along with the more typical markets, such as the New Yorker and Atlantic Monthly—no lower tier journals for us—we thought magazines like Playboy would be eager for our work. We switched from novel writing to short stories for a time and spent another fortune in postage, including the required “Stamped, Self-Addressed Envelop,” or SASE, that was required to accompany submissions back then. Our mailbox became the bearer of bad news. Over the course of several months, we filled a shoe box with rejection slips.

I now wonder if our foray into erotica didn’t have more to do with sexual frustration than anything else. I could probably count the times we were intimate that year on the fingers of one hand. While Rick rewarded me for literary production with a café con leche, churros or a trip to the Prado, I doled out my favors just as sparingly.

I no longer have any of those old short stories, risqué or otherwise. Perhaps it’s just as well.

I did write a book that year, a scant 50,000 words, handwritten in notebooks, which Rick then edited and typed, an original and a carbon copy. This was years before computers. We couldn’t afford one of the new-fangled typewriters that did have minimal word processing capabilities. When perfection wasn’t possible, we resorted to white-out, dabbing the paint on with a tiny brush, careful to avoid touching any adjacent letters, blowing on it until it dried, erasing the error on the carbon copy, then typing over it.

We boxed up my masterpiece and mailed it to a handful of New York publishers. Then we waited for news to arrive via the mailbox. I don’t recall how many times I sent out the full manuscript, or the first three chapters and a synopsis. I know I stopped when our money ran out and we had no choice but to fly home.

My unpublished manuscript now resides in my office, kept company by a few other failed attempts. It was a book that could have been written anywhere in the world, but that I wrote holed up in a Madrid apartment while the city—bursting with life and music and food I dreamt of trying, savoring, filling me up—happened six floors below.

That year in Spain I was always hungry. The hunger never left me.

As we prepared to leave Madrid, there was no one to give our household belongings to and we needed cash. We spread our one blanket on the sidewalk a few blocks down from the building and set out our meager wares. The tall apartment buildings on either side of the street kept us shivering in their shade. There was plenty of foot traffic on the busy avenue, but most people hurried past after giving us a nervous sideways glance or two. We did sell the typewriter and our stock of unused paper, to a student, at a bargain price.

Our charwoman walked by half a dozen times, muttering to herself. She must have returned to the building and told others. Neighbors began to troop past, generally pretending not to recognize us. They just wanted to see the crazy Americans for themselves, squatting on the sidewalk like gypsies. The señora came too. I don’t think she’d intended to stop but we called out to her. Head hunched, she pointed at our tea things, the pot and matching cups and saucers. I wrapped them in newsprint and set them inside her string shopping bag. She snapped open her leather change purse. We wouldn’t take her money. A tribute to the one neighbor we’d managed to befriend.

We flew home, broke, without jobs or prospects awaiting us and with zero publishing credits. Within a few months we were married. The marriage didn’t last long. When Rick eventually remarried, it was to his high school sweetheart, Gretchen. He hadn’t yet mentioned her back in 1978, when he insisted hers was the perfect name for my teenage heroine.

Summer of 2016, I returned to Madrid with my youngest child, on the eve of her eighteenth birthday, a month before she would begin her freshman year of college. It was my first time back. We stayed a week in an apartment I’d found on Airbnb, in the Malasaña district, while we toured the city and environs. If our lodgings on the Calle de la Princesa were a small studio, this was a closet. Two beds, one tucked into a narrow alcove above the other, galley kitchen and washroom, with a connecting passage not much wider than my hips. Up a rickety staircase, wood steps weathered by the centuries so they sloped towards the street, the building buffeted by metro cars passing beneath us, voices echoing up and down the air shaft. Lying in my snug berth, which also served as dining table and sitting room, I could imagine I was in a sleeper car on a train, safe and warm, rocked by a city that never slept. I would lie awake, mind buzzing, as I planned our next day, the light of my phone glowing in the dark, careful not to wake my daughter, asleep in her cubby above me.

At 24, I’d luxuriated in the drama of living in self-imposed exile. I’d fantasized a different life. One where I had important places to be, citas with lively, beautiful, creative friends in bars and cafes. We would cram round tiny tables or stand at the bar, faces close and animated, blowing smoke and gesturing with our hands.

At 62, the city was much as I remembered. It felt as if I saw more of it in one week, than I had over the course of an entire year. I was jostled on the subway, sat shoulder to shoulder with strangers in cafes, ordered our morning coffee and pan tostada con mermelada. I shared this place where I had once been young, where I had once had a dream, with my daughter. Whatever her dreams for the journey, for her future, may have been, she kept them close, as girls of seventeen tend to do. As for me, my dreams hadn’t changed much in forty years.

After a short ride on the Metro, we found the narrow apartment building where Rick and I had lived. A simple thing, to navigate public transportation. But it wouldn’t have occurred to my younger self. Though much of the money we’d lived on was the result of my having worked for it, and though I’d been out of my parents house for years, I behaved like a child. I went where Rick took me. I ate what was allowed.

I was often alone in the apartment. I fantasized about venturing out, meeting people, having adventures. I wanted to go to the cinema, to go dancing, to experience new sights and sounds and smells. I wanted to travel beyond Madrid. We were in Spain, for God’s sake. A country where I’d never been. But that wasn’t what we’d come so far to do.

I was reminded of my mother’s words. Before leaving for Spain that first time, we’d met for lunch. She pressed some spending money into my hand.

“Promise me you’ll travel while you’re in Europe, do some sightseeing,” she’d said. “Enjoy this opportunity. You may not have another. Life has a way of taking over.”

She was right, as mothers often are.

More than seeing the sights, or neighboring countries, I wish I’d realized the significance of the time and place. Madrid. 1978. La Movida Madrileña—the name given the cultural revolution that exploded in the aftermath of Franco’s death—in its infancy. I now imagine opportunities abounded, had we been open to them. Rather than writing about my own shallow past or attempting to create a literary journal from nothing, we might have connected with other struggling writers and artists, gone to readings and lectures at the least, or joined with others who were publishing new work, new voices that reflected the dynamic shift that was happening all around us, but to which we were largely immune. I might have immersed myself and used my words as a camera. Now I can only wonder how that might have been, all that I must have missed.

My daughter and I stood on the busy street and peered through the gilt and bronze doors at the row of mailboxes in the foyer, where I once made my daily pilgrimages, praying for letters, for the rare package from home. I imagined most, if not all, of the residents who had lived there that year were now gone. Our neighbor surely, and the frowsy, stooped charwoman who swept the stairs top to bottom each day, slopped them with a wet mop and picked up the trash we left just outside our door. I would hear her pausing to catch her breath when she reached our landing on the topmost floor. No matter what I was doing, I would freeze, as if I’d been caught out. She was twice, perhaps three times, my age, sweeping, hauling, working, while I scribbled in my notebook. I sensed her bleary eyeball at the keyhole, pressed to the slot. I’d wait for her heavy clump on the stairs before I unfroze. I can still hear her mother, the portera, who must have been ninety, hollering up the stairwell with some new task for her daughter.

I still have my first passport, issued in January, 1978. In the photo, I have the faraway gaze of a winsome poet. Hair frames my face, a full Afro poof that reaches the tops of narrow shoulders. It expired long before I would need another passport. I only know of one photo from that year in Madrid. I’m in our tiny kitchen, hunched and forlorn. I’m wearing the same sweater as in my passport photo, but the light in my eyes, and that great rounded halo of hair, are gone. As a cost-saving measure, Rick had cut my hair. I resembled a badly-coiffed poodle. After that haircut, I never left the apartment without covering my head. I wore my one threadbare yellow satin scarf, wrapped tight and pulled flush with my hairline.

As the days in Madrid passed, the language returned to me in ways I hadn’t expected or hoped for. I found myself thinking and writing journal entries in a jumble of intertwined Spanish and English. I was reminded of the heady sensation of discovering other sides of my personality, of losing the shackles of my English-speaking self. Every language has its own rhythm and cadence. There is a freedom in occupying a different linguistic self for a time. I always imagined my Spanish-speaking self enjoyed a freedom from many of the constraints my other self was bound by. She was a better dancer and singer. She didn’t worry so much about her hair. She gestured with her hands and laughed more boldly. She ate what she wanted, when she wanted, and she did it with gusto.

I’ve just finished another book about coming of age in the sixties, and being in my sixties, among other things. There’s nothing veiled, thinly or otherwise, about it. It’s full-on memoir. Like the book I wrote in Madrid, it was also written in a year. One thing I’ve learned, these things can trail on forever if you let them.

So much has changed. Computers of course and software to make it easy to move things around. Home printers. The internet for research, fact-checking and for finding agents and publishers, if and when that time comes. Thousands of literary journals from around the globe, all only a few keystrokes away.

In 1978, rejection slips arrived in the envelopes we’d provided. Now, it’s an e-mail, at best. I’m hoping we had the courtesy to respond to the young poet from Gibraltar, to explain to him that we weren’t rejecting his poetry, but that our project hadn’t come to fruition. I wish I’d saved my box of rejection slips from that year. There were a few handwritten notes from editors amongst them, including some for my novel. I didn’t know enough to have appreciated how rare that was—a learning opportunity—that an observation or suggestion, no matter how tersely worded, might have held the key to revision. I only saw rejection, another slammed door, end of story.

Some things haven’t changed. A book, or any other writing, is still accomplished one word, one page, one day at a time. It still comes from inside, no matter how expansive or limited one’s worldview. I might have written this latest one in Madrid or Paris or New York City. That might have been nice. But I wrote it in my suburban Sacramento home, mostly on the couch in my front room, with a view of our tree-lined street, my geriatric dog in a basket at my feet, the black cat kneading the cushion beside me.

At 24, I hoped to make my mark, to be somebody, to matter. At 64, that would still be nice. But I won’t be surprised if it doesn’t happen. Nor will I be so devastated, that I don’t try again for another forty years. I don’t have that luxury. I also know that, in many of the ways that count the most, I’m already there.

As for Madrid, perhaps I’ll write another book there one day, financed by the advance from this newest venture. Hope springs eternal. Or dies hard.