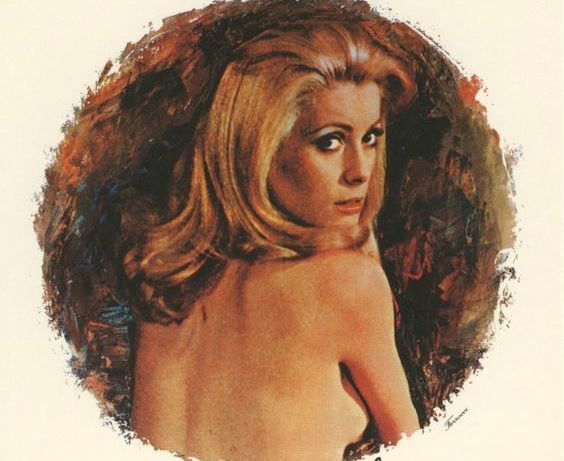

It’s not enough to see Belle de Jour as an erotic classic. Such an appellation might be justified of a film preoccupied with a conventional cinematic rendering of soft focus bodies breathing heavily over a melodious soundtrack. Not so Belle de Jour. Certainly it is an erotic picture, but not for the reasons one might think. Above all Belle de Jour can be an infuriating film and it’s not difficult to see why. For audiences the same questions invariably arise: why is Catherine Deneuve so blank? What was in the fat Chinaman’s lacquered box? Such questions actually tell you everything you need to know in order to understand the film, in as much as Buñuel intended you to at any rate. Its slipperiness is deliberate. That’s because the real subject of Belle de Jour isn’t eroticism in the basic sense of the word. Buñuel knows eroticism is all in the mind, that it’s psychologically dangerous as much as it is seductive. He knows that it tells us more about ourselves than we would perhaps care to admit.

Bourgeois housewife Séverine Serizy (Catherine Deneuve), is trapped in a sexually stifled marriage to handsome but conventional surgeon Pierre (Jean Sorel). Séverine is a masochist who, in order to fulfil her secret penchant for rough sex, takes a job at a brothel run by Madame Anaïs (Geneviève Page). She works from two to five and takes the pseudonym of the title. Soon enough however living out her private fantasies proves problematic back in the real world when she falls in love with the dangerous, metal-toothed gangster client Marcel (Pierre Clémenti). From such a potentially melodramatic narrative Buñuel extracts a playfully savage account of human nature at its most inscrutable.

Now, some critics might suggest that any eroticism present is clearly that of a director indulging in his own misogynistic interpretation of female masochism. Perhaps. Certainly, it can be somewhat problematic to appreciate Belle de Jour from a feminist perspective, since Buñuel seems preoccupied with perpetuating the image of the masochist who perversely invites the patriarchal debasement of her ‘goodness’. What does Pierre Clementi’s gangster represent if not the embodiment of the masculine domination required to liberate Séverine’s sexual pleasure? Moreover, not only does Buñuel seemingly advance the ultimate male fantasy, he insists on punishing Séverine for her perversion by killing her lover and leaves her with a crippled husband. But this superficial reading is only one of the myriad refractions this complex film produces.

Understanding the film hangs entirely on the intriguingly impenetrable Séverine. Nothing escapes from Denueve’s beautiful but detached countenance, she remains unreachable, beyond the comprehension of the audience. But she’s not supposed to be understood. Buñuel is not in the business of providing simplistic psychology, so it comes as no surprise to hear Deneuve recount in interviews that Buñuel’s directorial instructions to her amounted to ‘Don’t do anything’. His motivation for portraying Séverine in such a way is clear—if we can’t know Séverine we are left with frustration. Frustration is what Buñuel is interested in here. Buñuel isn’t interested in titillating the audience by allowing them to see Catherine Deneuve pelted with mud or raped by two carriage drivers upon her husbands instruction; or rather, he is interested in showing the audience this, but not out of prurience. There is a subtle purpose and complexity to Buñuel’s staging of these sexual scenes. Yes, he’s happy to indulge his own fetishistic interest in a well turned ankle, or carefully construct an immaculate image (courtesy of Yves Saint Laurent) of the refined but repressed bourgeois with a hint of smouldering sexuality beneath the surface, only to defile that image throughout the film. He goes to great lengths to push Séverine into knowableness, such as when an early client strikes her on the face. Séverine doesn’t react. The only flaw comes in a few momentary childhood flashbacks which insinuate abuse, which are actually unnecessary. Still, Séverine remains out of reach. Buñuel thwarts the audience at every turn. The question is, to what purpose?

The answer lies in the presentation of fantasy itself, not the content of that fantasy. When questioned about what was real and what wasn’t, Buñuel answered such questions playfully, saying, ‘I myself couldn’t say what is real and what is imaginary in the film’. From the opening scene, which startlingly presents Séverine’s rape fantasy as an extreme intrusion upon her reality, Buñuel establishes the parallel worlds Séverine inhabits. Buñuel’s natural terrain is psychological inevitability versus moral logic. For him the former was infinitely more truthful than the latter, which he acknowledges in Belle de Jour. With a certain amusement Buñuel slyly subverts the linear misogyny in the narrative’s ‘reality’ by espousing the aforementioned moral logic through Henri (Michael Piccoli), Séverine’s aggressive admirer, whose overt attempts at seducing her ‘purity’ she rebuffs. Even when Henri later shames Séverine by turning up at the brothel, the disgust of the patriarchal morality cannot make Séverine a victim. She escapes its attendant guilt and shame by merging fantasy and reality by the end of the film when Henri proposes to tell Pierre all about his wife’s day job. Séverine steps out onto the balcony, hears the jangling bells which have inexplicably accompanied her fantasies, and is joined by her husband, restored of his sight and use of his legs.

Belle de Jour articulates an inexorable reality of human nature—people do what they know how to do. In so doing it releases sexual repression and frustration from the bondage of morality and moral judgement. This is why Belle de Jour remains such a marvellous picture. Frustrating yes, but marvellous.