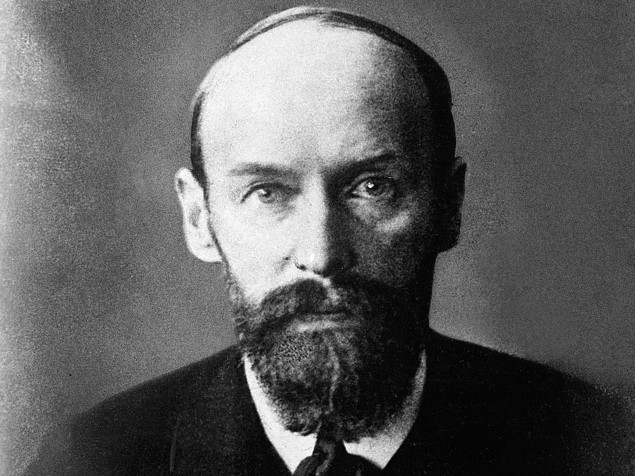

In his comparatively brief life, Christian Morgenstern, born 1871, was a writer of sketches and short pieces (feuilleton) for newspapers, an editor, among others, of Robert Walser, and a translator of Ibsen’s poems and lyric dramas. He also published a series of collections of lyric poems which formed the centrepiece of his serious literary works, along with aphorisms and brief reflective prose. It is the three volumes of nonsense poetry though (the Galgenlieder) that he published in the decades before the First World War that secured Morgenstern’s place in anthologies of 20th century German literature. Poems that he himself saw as a diversion, an entertaining aside from his serious work.

Morgenstern died in 1914, and the immediate post-war period saw the publication of a biography, a volume of selected lyric poetry, and a volume of prose (Stufen, or Stages), all overseen by his widow and designed to present a spiritual journey that culminated in the adoption of the thought of Rudolf Steiner. It was the Galgenlieder though that became increasingly popular during the 1920s, making connections at the same time with the European avant-garde, a direct precursor to concrete poetry, recited at gatherings of DADA artists in the Switzerland of the war years. It was the Galgenlieder, and not the lyric poems, that became, more widely, part of the twentieth century preoccupation in philosophy and literature with the nature of language itself.

In the entertainment of the Galgenlieder poems, Morgenstern invents an architect “who removed the spaces” from a fence “and built a residence” (in Max Knight’s translation, first published in 1963), also Korf’s joke, that like a slow burning fuse wakes the listener up hours later “smiling sweetly like a well-fed baby”. Elsewhere a wicker chair gives away someone’s daytime thoughts at night in “cracking sounds and crackling sounds”, and in other poems we find the land of punctuation, a moon sheep, and an almost Steven’s-like Raven Ralph who ‘will will hoo hoo’, along with the verbal nonsense of ‘Das Grosse Lalula’,“Kroklokwafzi? Semememi / Seiokrontro-prafiplo”. Turning from these to the selection of lyric poems published in 1929, it is hard to believe that they are written by the same person. The poems, arranged under headings such as ‘The Realm of Night’, ‘Images of Nature’ and ‘Fulfillment’, look back to the romantic poetry of the previous century, recording, for the most part, significant moments of feeling and reflection in language that is certainly sincere, but without too much in the way of engaging images or metaphor.

In a sharply written biography published in 2014, the centenary of Morgenstern’s death, Jochen Schimmang suggests that it would be a mistake to look for any consistency in Morgenstern’s life and work, that two temperaments simply existed side by side: the lyric temperament that dominated his literary ambition, coexisting with that of a philosopher or critic of language (“ein sprachphilosphisch-sprachkritisches Temperament”). By his own account, published in the prose excerpts of Stufen, Morgenstern was greatly under the spell of Nietzsche in his early twenties, and may have been influenced, for example, by the language scepticism of an early essay ‘On Truth and Lies in an Extra-Moral Sense’, in which Nietzsche suggests that language is rooted in dead metaphors that mean that it only seems to speak directly of the world. Morgenstern certainly became preoccupied, like the young Samuel Beckett, with the now almost forgotten critic and writer, Fritz Mauthner, who pushed to an extreme the sceptical view that abstract, generalising language can never truly connect with the particularity of the world of experience, that language and world diverge. A view also explored at the start of the last century in the brilliant description of the failure of language found in Hugo von Hofmannsthal’s ‘Lord Chandos Letter’. In 1906, at a time when Morgenstern was reading Mauthner’s recently published Beiträge zu einer Kritik der Sprache (Contribution to a Critique of Language), he asks in a letter to a friend if language “can help us towards any kind of real knowledge”.

Morgenstern’s response to Mauthner and language scepticism is the brilliance of the Galgenlieder. Mauthner frees the logic of language from the world, but in the Galgenlieder, Morgenstern reduces Mauthner’s scepticism to a kind of absurdity in which the separation of language and world creates humorous nonsense. Looked at this way, the Galgenlieder present the flip side of the view that dominated much 20th century philosophy of language, that sense or meaning in language must ultimately rely on the way that words connect to things that can be either true or false. To have sense, the sentences of a language most refer in some way to facts or events in a possible world. Nonsense, and nonsense poetry, divorced from any possible world in which things can be true or false, belongs to the shadow side of sense. Not long after Morgenstern’s death, working on his Tractatus as an Austrian prisoner of war, Wittgenstein aimed to show how sense and nonsense shows itself in the logic of language. In one of the propositions of the finished work, he wrote that “All philosophy is a ‘critique of language’ (though not in Mauthner’s sense)”.

In the Galgenlieder, the spaces in the picket fence become the non-existent things the architect steals to build his (non-existent) house, and ordinary names are re-arranged to create equally non-existent creatures, so that a chicken hawk becomes a hawk chicken, with relatively predicable consequences, and the merging of disparate names invites the description of the moonsheep and others. The actions of Palstroem and Korf are described in a number of poems, but they are each no more than their names, so that in ‘The Police Enquiry’ for example, Korf can only respond to a form by stating that he doesn’t exist. The poem ‘Cousin Kinkel’ simply asserts that nothing can be said about cousin Kinkel. As the philosopher Saul Kripke argued later in the twentieth century, names are not in themselves descriptions of anyone (real or fictional). A name tells us nothing except that an act of naming has taken place. In other poems,the autonomy of language without reference can create particular non-events, so that Palstroem cannot have been run over, for example, because the words of the law do not permit cars in the place where the accident occurred (Palstroem concludes, as a result, that he was not run over). In yet more poems, the logic of language without world is displayed in the more conventional nonsense (or nursery rhyme) narration of physical but not grammatical impossibilities, so that setting the hands of a clock to go backwards, reverses the flow of time, or a pair of glasses is invented that mercifully summarise a text before the eyes of the reader. More conventionally, objects become animated and impossible transformations occur, so that humans, for example, are trapped on paper on a housefly planet.

The casual violence and grotesquery of poems like the last also places the Galgenlieder closer to conventional nonsense or nursery rhyme. Violence can be enjoyed because it takes place without consequence – there is no possible (even imagined) world in which there can be consequences. In poems like these, the entertainment of Morgenstern’s invention comes closer to the amoral entertainment of say, Lear’s limericks, or the casual violence of Alice in Wonderland. This is particularly true of the earlier Galgenlieder, which Schimmang explains had their origins as lyrics for songs sung by a youthful Morgenstern with friends in gatherings, held in a bar outside Berlin on what was once a gallows hill. None of this is dream or nightmare though. As Elizabeth Sewell explains in her classic study of English nonsense, the nonsense poem combines the pure play of language with a complete control of words. The precision of invention and transformation that marks nonsense poetry displays a logic which is quite different from uncontrolled dream logic, with its condensation, and sudden shifts and ambiguities inviting interpretation. In the conscious, controlled entertainment of the nonsense poem, there is nothing to interpret.

If the Galgenlieder are modernist though in their deliberate, self-conscious use of language freed from reference, Morgenstern himself was anything but a modernist writer in his other works. His lyric poetry, in the romantic tradition, was very much a response to a real, felt world. More than that, it is clear from Schimmang’s biography, that despite the precarious existence of his working life, relying on commissions for articles and translations, he was motivated throughout by the need to find and hold on to a world view opposed to the rapidly industrialising, bureaucratic Germany emerging around him. Distancing himself from Nietzsche, for a while he endorsed the reactionary conservatism of the now largely forgotten Paul de Legarde. Later he came to adopt the mystical religious conviction that the presence of God was to be found in all things, recording his own mystical experience in a fictionalised account published after his death in Stufen. Finally, and most completely, in his last years he become a devoted follower of Rudolf Steiner, in his case, quite literally, travelling from city to city, despite the increasing severity of his tuberculosis, in order to listen to Steiner’s lectures. Morgenstern was by nature a believer, a disciple, something only strengthened by the difficulties of an illness which placed him increasingly at the edge of the world of the early twentieth century, as he moved from sanatorium to sanatorium, rest cure to rest cure.

As a result, the Galgenlieder remained a kind of light verse for Morgenstern, written for entertainment, and they have the anonymity, the deliberate exclusion of the author’s self and personality (idiosyncrasy), which Auden saw as a key characteristic of light verse in his introduction to his Oxford Book of Light Verse. Morgenstern is not at all interested, for example, in the strategy of reticence to be found in Lear’s nonsense songs, in which nonsense is used to suggest emotion, while revealing nothing of the life of the writer. For Morgenstern, nonsense is always entertainment, and something less than literature. In one of the remarks collected in Stufen, he writes in 1906 that “The nature of my humour pains me. My constant question – whether all humour contains an element of the philistine”.

Anonymity, and the exclusion of the lyric self, become though energising elements in the subversive literature of the twentieth century, which can claim kinship with Morgenstern’s Galgenlieder, literature uncomfortable with received ideas and beliefs. Not just DADA, but the later – still humorous – post Second World War poetry of the Austrian Ernst Jandl, for example, or the more bitter, anarchic nonsense present in the writing of Gunter Eich. The Galgenlieder became modern, and their author a modernist with them, despite his own self-understanding. In their self-conscious use of technique, and the exploitation of the logic of linguistic expression, the nonsense poems have remained relevant, suggesting a path to a poetry which abandons any confessional, or truth telling mode of expression, to generate a poetry, which, like the Galgenlieder, can work without reference to any stable reality.

Works referred to:

By Christian Morgenstern:

Gallows Songs and Other Poems, selected and translated by Max Knight. Munich: Piper, 1972.

Auswahl [Selected poems], edited by Michael Bauer and Margareta Morgenstern. Munich: Piper, 1929.

Stufen: Eine Entwicklung in Aphorismen und Tagebuch-Notizen, edited by Margareta Morgenstern and Michael Bauer. Munich: Piper, 1918

Also:

Jochen Schimmang, Christian Morgenstern: Eine Biografie. St. Pölten: Residenz Verlag, 2013

Elizabeth Sewell, The Field of Nonsense. London: Chatto &Windus, 1952.