Fading Horizons:

Regarding the Decline of American Mall Culture

For those of us who grew up during the 1980s, the indoor mall—first etched into the landscape by architect Victor Gruen three decades earlier—was a hub of life and teenage social activity. At the mall, we enjoyed a shared destination, a space for interaction where shoppers could display their purchases—all the accoutrements of fading upper middle class life—and share the company of peers. Born of postwar prosperity, malls emerged to augment the suburbs, which, although comfortable, were largely unsuitable for community gatherings. Gruen’s innovation helped to solve this problem, transforming car culture into mall culture, as newly mobile suburbanites drove off to shop and meet for lunch. If we are to understand this phenomenon and its current decline—within the context of new, emerging social spaces—a glance back at the age of mall building and middle class growth is useful. Beyond this, we can consider the interpretation of Walter Benjamin’s view on history, as well as the mid-century conception of retail space. These viewpoints contrast, in a revealing fashion, and exhibit an interesting synthesis when we read them alongside the medium of film.

While Benjamin warned of the chaos and deterioration proffered by industrialized life, postwar builders saw nothing but the opportunity for wealth. The visual aspects of film resolve these opposing perspectives, first in the commercial/industrial utopias articulated by Fritz Lang in his 1927 film Metropolis, and, nearly a century later, by the poignant chronicles of videographer Dan Bell in his “Dead Mall Series.” Taken together, these discourses comment on American mall culture, providing images of its downward momentum in context, from which we can draw a conclusion: the end of “the American Century,” and the decline of our consumer spending-driven economy—as well as the transformation of social engagement imposed by technology—call for a radical reassertion of third spaces, not only for the sake of commerce, but for the preservation and continuance of community life, a reinvention which must incorporate the renewal of massive vacant mall properties. Let’s begin with a look at the birth of the indoor shopping center and consider some of its more compelling social contexts.

The Vision of Victor Gruen

In 1950, the Allied Stores Corporation opened Northgate Shopping center in the Seattle, Washington area. Recreating a downtown configuration, a thoroughfare was lined with stores, and parking was located on the outskirts to exclude cars from the shopping environment. (1) Although a significant number of retailers could be accommodated, the problem of walking great distances in order to shop created an obstacle, since most patrons had grown accustomed to the convenience of driving. Creating an alluring form of architecture was essential if the problem was to be solved. Consumers wanted shopping districts that would accommodate their vehicles. It was a challenge, but this was an age of economic optimism and innovation, and designers embraced it. They would use aesthetically pleasing spaces to direct consumers to their destination, and accommodate their cars, in grand style. And this had everything to do with the spirit of the times.

In general, mid-century modern architecture was expansive and exuberant with its elongated lines, defined horizontal views, and bright spaces, a choreography of subtle textures emphasizing peace and the enjoyment of new prosperity. It was nothing if not a salient cultural moment. And the vision of Victor Gruen, whose innovative retail designs would set the industry standard, would grow out of this momentum, as he created America’s mid-century shopping culture. In short, he translated the postwar attitude into a unique solution for retailers: car friendly districts of commerce. With the Northland Shopping Center in suburban Michigan, completed in 1954, Gruen began to develop the architectural form for which he would be best remembered—to his eventual consternation. In Gruen’s mind, the key to reinventing the suburbs as a shopping destination was simple. In 1948 he stated: “We are convinced that the real shopping center will be the most profitable type of chain store location yet developed, for the simple reason that it will include features to induce people to drive considerable distances to enjoy its advantages. (2)

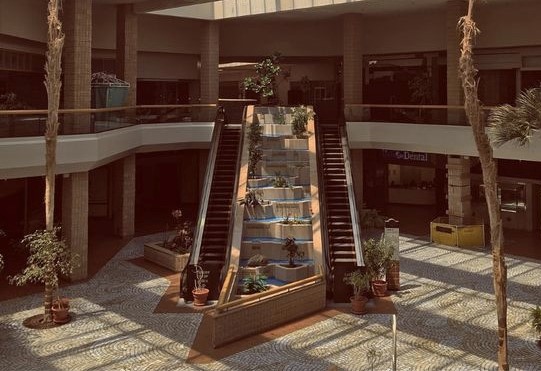

[Gruen Associates]

And what were those advantages? After wartime rationing was no longer an impediment to comfort, and jobs were plentiful, convenience was a primary consideration, a key advantage of modern life. Although suburban housing developments were generally more comfortable than their urban counterparts, the former lacked the conveniences of city life. However, far from welcoming new shops into their neighborhoods, suburbanites had to be persuaded of their advantages, and Gruen obliged. Even before creating the American mall landscape, he reminded suburbanites that the individual department stores he was designing would offer them new services and opportunities for socializing. (3) The corner markets and newsstands of the city, where people could meet to discuss events of the day, were considered to be too inconvenient, even somewhat anathema to the goal of living apart from downtown culture. In the suburbs, new shopping districts would offer dinning options and meeting spaces, as well as innovations like Gruen’s rooftop parking designs. Moreover, these spaces emphasized a separation from urban life. This was indeed a revolutionary enticement, but his main innovation had to do with placing an anchor at the center of the shopping “mall” and surrounding it with concentric circles of retail space. The problem posed by walking a lengthy “main street” configuration had thus been solved. Later, in the nation’s first fully enclosed and climate-controlled mall, Gruen would revise this design to incorporate a second anchor store. For the first time, the American retail landscape had a formula for shopping center design, one which would remain standard for decades to come.

In 1984, Jerry Jacobs called the mall “a conglomerate of retail stores linked together by enclosed walkways or corridors. Each end of the mall has its . . . major national department stores . . .” (4) Herein lies the basic structure of the American mall we know so well; two “anchor” stores (one at either end of the structure) directing foot traffic through a corridor of smaller establishments, the vision of Gruen taken to a new level. Even beyond the aspect of commerce, however, the total immersion shopping experience created a unique environment for socializing.

Jacobs reminds us that the mall offers a predictable setting, where the hazards of urban life are excluded and suburbanites can gather, comfortable in the knowledge that “nothing unusual” happens at these indoor shopping centers. (5) Of course, that ideal has changed over the years, but the early promises issued by Gruen for social spaces, as well as his vision of enticing people to drive considerable distances to shop, remained viable for several decades. Additionally, these shopping structures offered a new concept of middle class life; if the advent of planned obsolescence, during the early part of the century, had conditioned people to identify themselves with their cars and clothing, shopping had become a full-fledged lifestyle by the 1950s, an emphatic statement of upward mobility. That many people have gone into debt to fund this way of life is, perhaps, the greater part of the shopping legacy, this and the many vacant malls that now encumber us. And yet, shopping was not the only aspect of mall life; amusement and diversion were also key devices.

With the indoor mall, the activities of shopping and entertainment began their half-century-long romance, a relationship which has only begun to cool in recent years. Carousels and playgrounds for children, fashion shows, and movie theatres (beginning in the 1960s), came to exemplify shopping as a lifestyle of enjoyment and diversion. Malls of the era were, quite simply, how the middle class lived and aspired to embrace the promises of a vibrant economy. Underwriting this trend was an attitude, one which can be understood best through the lens of previous centuries, as we examine the rise of consumerism, as well as the theatrical conception of utopian city life.

Historical and Philosophical Considerations

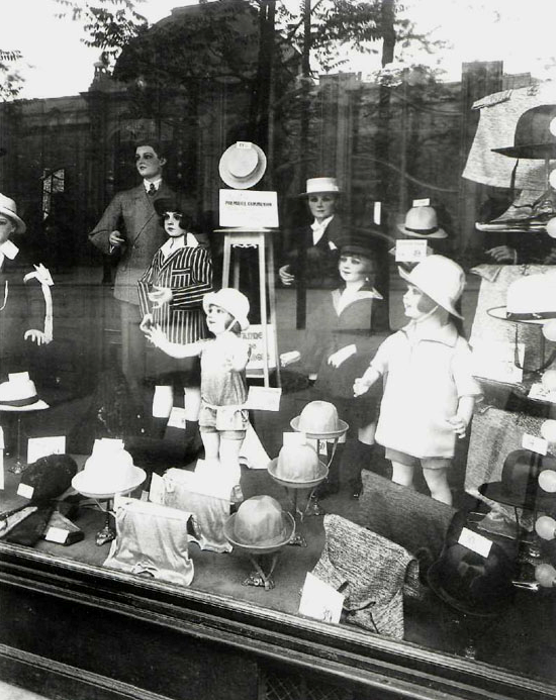

In “Circumstantial Evidence: Shops and Display Windows in Photographs by Eug ne Atget, Bernice Abbott and Walker Evans”, Ingrid Pfeiffer explores modes of commodity representation, how perceptions of shopping were beginning to develop during the early twentieth century. She notes that Atget was beginning to focus on the items and locations associated with mercantile life, rather than the buyers and sellers themselves. “It is not the portrait of the shopkeeper that forms the subject of the photograph Eug ne Atget took in 1902 . . . ” Rather, it was the delicatessen in the background. (6) In another example of his work, we see an early use of mannequins, where the photographer highlights the secondary role played by humans, as people became mere reflections and representations of the commodities they cherished.

[Eugène Atget]

In the early days of the century in Europe, as well as in the United States, merchandise was beginning to be viewed as an autonomous aspect of life. Pfeiffer goes on to describe Atget’s sale of photographs to artists, those who wished to retain a clear and literal representation of merchandise for their own creative work. Regardless of abstraction and analysis in relation to the objects—whatever expressive renderings the artists would create—commodities had been acknowledged for their autonomous role in the new century. Things had a life of their own. So elementary and consistent were the pieces of merchandise in his photography that “Atget’s analytical visual angle was always the same, and in the course of time human individuals almost vanished completely from his repertoire.” (7) This speaks loudly to the overall relationship of human beings to their objects of consumption. Beyond this, we can go further and question larger aspects of material culture and the ways in which it represents the progress (or regression) of society.

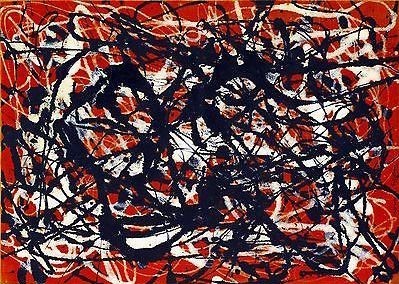

Susan Buck-Morss considers the appearances and realities of rising consumer culture in The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. As the necessities of daily life, as well as a host of luxury goods, were beginning to disappear behind mythic representations, questions of perception arose. “How could this phantasmagoria be seen through? How could the mythic metaphors of progress that had permeated public discourse be umasked and exposed as the mystification of mass consciousness, particularly when the big-city glitter of modernity seemed to offer material proof of progress before one’s very eyes?” (8)

One way to explore this question is to move from utopic to dystopic representations. In Fritz Lang’s Metropolis, the city—the setting of labor and material acquisition—assumes power over humanity, not only by imposing the conditions of labor and insisting on obedience and conformity (as people are subsumed into machine life), but also by the intervention of magic. Here, we consider “Metropolis: City, Cinema, Modernity” by Anton Kaes: “This sudden metamorphosis reveals Metropolis’s underlying ideology, which associates machines with man-eating monsters and the inventor Rotwang with black magic.”(9)

The city of entertainment, commerce, and luxury is also, in its deepest essence, a darker realm where the grueling labor of industrialization threatens to engulf rather than uplift humanity. Lang’s vision warns of widespread destruction, of a spiritual as well as physical nature. In contrast, Benjamin’s concerns are more immediate and prosaic, if no less urgent.

In the end, a city litters history with residue, even more than it contributes lasting monuments. And Buck-Morss reminds us that Benjamin considered the former to be worthy of analysis, even a bit more than the latter: “Where the megalomania of monumental proportions, of ‘bigger is better’ equated both capitalist and imperialist expansion with the progressive course of history, Benjamin sought out the small, discarded objects, the outdated buildings and fashions which, precisely as the ‘trash’ of history, were evidence of its unprecedented material destruction.” (10)

When we see millions of square feet of erstwhile retail space moldering, these ideas become highly relevant—urgent, even. The Mall of American, which, as of this writing, still graces the landscape of Minnesota, stands as a testament to the “bigger is better” ethos as its monumental dimensions produce tons of litter, perhaps hinting at the establishment’s eventual demise. This structure teeters under the weight of self-parody, but it is not alone; clearly, dozens of decaying malls and empty parking lots exemplify, in nearly poetic terms, “unprecedented material destruction.” Teenagers of the 1980s, accustomed to comfort and upward mobility, are likely a bit surprised and grieved to see, as they enter middle age, the hollow remnants of mid-century prosperity. Indeed, the decline of mall culture corresponds with urban decay in a complex relationship of haves and have nots. Outwardly, however, revitalization efforts in large cities have been reversing the trend, to some extent, as once depressed infrastructures are “repurposed” to meet the needs of changing demographics.

Urban Renewal in Perspective

The development race was, ostensibly, between the suburbs, with its new homeowners and emerging car culture, and the declining urban landscapes. And, like a savvy architect, Gruen was able to step away from his suburban projects to offer urban planning commissions a way to save their downtown shopping districts.

In the unlikely setting of Fresno, California, Gruen began to address the issue of urban renewal. His relationship with the city was chronicled by Victor Gruen Associates in a 1968 documentary entitled, Fresno, A City Reborn. The firm aspired to create a fresh environment not only for commerce, but also for government and finance. The narrator states: “Great cities enrich our lives intellectually, socially, as well as culturally. And they provide opportunities for entertainment and relaxation.” Ironically, the great promise of the suburbs, which Gruen had helped to articulate and capitalize on a decade earlier, was being repurposed to gain a new client—the one he had helped to dismantle in the first place.

Fulton Mall, the fruit of Gruen’s labors, was enthusiastically dedicated in 1964, but the mood quickly changed. Beautifully designed with public art, gathering spaces, and major retailers, its halcyon days were short-lived. This revitalized area—a center reserved for pedestrians—gradually began to decline as the population shifted, eventually being eliminated in 2013, when the Fresno City Council voted to re-introduce vehicular traffic in yet another bit to improve the area. The pendulum of renewal and decay swings continually, rendering theories and strategies a necessary aspect of community planning. One constant seems to be the issue of changing demographics. When large numbers of people move, either from a new infusion of prosperity, or in the hopes of finding work, they take their business with them. Indeed, city planners and architects are nothing if not masterful at moving populations around to bolster struggling economies, then moving everyone back to repeat the process in the newly depressed region. And although there are numerous complexities involved, from a socioeconomic standpoint, this back and forth movement of resources appears to be a basic pattern, a game with clear winners and losers.

When renewal occurs, the question of who exactly benefits from new shopping centers and expensive housing options remains a point of contention. In the end, history could judge the development/renewal model to be no more than a cyclical movement of wealth and resources, and not an actual reinvention of socially and economically depressed areas. Moreover, the closing of numerous malls, once hallmarks of prosperity and growth, signals a larger issue to the entire country, which begs the question: is this nation actually prosperous? To some theorists, prosperity still lingers, but only for a limited segment of society.

In an address to the Urban Land Institute, at their fall, 2017 meeting in Los Angeles, theorist and professor Richard Florida articulated a new issue, related to his book The Rise of the Creative Class. He admitted that urban renewal—quite impressive in a number of cities—is only an advantage to the creative class, roughly a third of the population, this, while the remaining two thirds struggle to make ends meet in expensive environments where they generally work in a service capacity. Problem. The New Urban Crisis, which explores the vast socioeconomic divide, chronicled Florida’s solution, related, as it is, to age old questions of opportunity and equality. Here, we come to the issue of theory and its often contentious relationship to practice. The key has to do with the many contingencies which must be considered when dealing with human beings.

Theories surrounding urban renewal will always be required to expand and contract in order to address the human factor; simply devising academic ways to refurbish the built environment is not enough. The complex needs of a given population will, eventually, be the cause of failure or success when rehabilitating our commercial and residential centers. Beyond this, theories of renewal require the strength of visual images and experience to be truly effective when converted to the realities of practice. I mention this because the dozens of mall ruins that exist in America attest to the gravity of economic decline, a situation which often eludes even the most eloquent and far-reaching theories of revitalization. Here, the strength of images is highly relevant. To espouse ideas is one thing; to walk the ruins of once thriving environments is another. To gain further perspective, and understand just how widespread the collapse of mall culture is, it’s useful to study the work of videographers.

As of this writing, videographer Dan Bell publishes “The Dead Mall” series on YouTube, walking viewers through the retail ruins—and near ruins—we might not otherwise see, the missing rooftiles, stained carpets, broken windows, unoccupied food courts, and boarded-up shopfronts that speak to the phenomenon of commercial decay in poignant terms. In city after city, Bell documents the decline of once thriving malls on a personal level. Again, for those who grew up during the 1980s, the experience of viewing mall ruins is jarring, a sad bit of nostalgia his videos capture wonderfully. In particular, Bell’s footage of the Galleria at Erieview in Ohio offers striking views of center courts, dining areas, public art, and hauntingly vacant retail spaces. To date, he has visited roughly forty properties, panning the grand structures of the previous era, raising urgent questions about the future. Indeed, it’s staggering to note that tens of millions of square feet—of once prime retail space—have been impacted, portions of which have been repurposed, many of which stand vacant to this day. Even beyond the economic issues, which are substantial, the social needs of residents are also at stake. Bell captures the urgency of this situation quite effectively. In addition, his video narrative ties back to the previous century, reminding us that Metropolis spoke to the rise of technology and the transformation of human life in richly theatrical terms, for good reason; change was on the horizon, and its impact promised to be compelling. How would technology, and the drive to acquire more goods affect daily life and the quality of social interactions?

In 1927, the darker aspects of industrialization and the factory system were uppermost in people’s minds. However, the advent of planned obsolescence created a nation of consumers, ironically trapping laborers in the drudgery of the workplace to purchase necessities as well as the accoutrements of status. As of the early 2000s, Bell commented on this narrative to reveal the megalomania of consumerism—much of which is related to high technology—as it begins to undermine its creators, much like the flesh-consuming machines of Metropolis.

In part, “dead malls” are the result of internet commerce which has rendered trips to the marketplace a bit obsolete, convenience always being a commodity in and of itself. Even so, there are affluent areas where shopping and dining remain available to those of “the creative class,” prosperous centers where foot traffic is still the rule rather than the exception. But the mechanisms of “progress” do tend to feed on those who live on the fringes, even if such people constitute the bulk of the population.

Retail Images in Context

More than anything, mall culture at its height was a visual experience, as is the phenomenon of its decline. With that in mind, we have explored some useful images and ideas. From photographs and film footage, to the warnings of Benjamin regarding the illusory aspects of progress, the decline of mall culture can occupy a number of contexts. Even beyond the elegant theories of the moment, is the necessity to transform vacant malls into useful third spaces, posthaste. When decay goes unchecked, it has a pernicious way of spreading beyond all reparation.

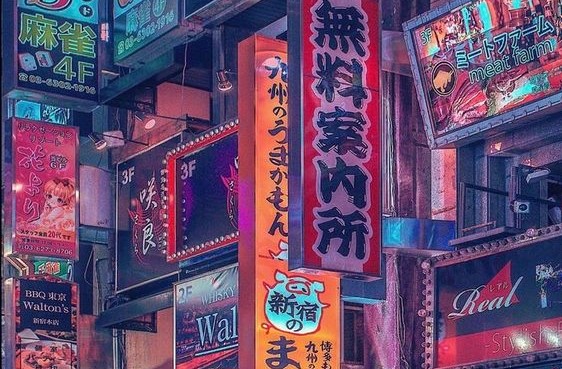

With this in mind, some malls have been remodeled into office parks, where fitness centers and restaurants serve workday crowds, a renewal model which might stand the test of time. But the underlying theme of illusion remains a compelling issue; the glamour of consumption comes at a price, and even in the best of times, only a small segment of society benefits from elegant environments. Moving into the midst of a new century, economic uncertainty will likely remain with us into the foreseeable future; even when commercial spaces are reinvented, the bright optimism of previous decades is likely to be missing. The new aesthetic of digital life does seem related to the symbols and images of Metropolis.

Today, we know the hazards of high technology environments—relentless surveillance, the buzz of drones, crowds shuffling forward while staring blankly at their phones. But the shadows of malaise and the conscription of society (stark images of Fritz Lang’s dystopia) were nowhere in evidence when Victor Gruen began to build his malls in the cheerful mid-century landscape. With this in mind, perhaps we can say that the decades of mall culture were no more than a fleeting aspect of social history. Time has shown that our grand cities produce vast amounts of despair and waste, even as they promise to fulfill our dreams.

As the horizon line fades for mall culture, we have a number of images from the past to consider, aesthetics and ideologies which may help to bolster newly revitalized commercial and social spaces. After all, the needs of human beings for goods, services, and pleasant community environments (third spaces) have not changed in the last century. Ultimately, injecting cash into beleaguered landscapes may prove fruitless. However, the entertainment hub/town center model seems to be the design of the moment, perhaps destined—in all of its sunny optimism—for the eventual fate of mid-century shopping malls.

Endnotes:

- Nancy Cohen, America’s Marketplace: The History of Shopping Centers (Lyme, Connecticut: Greenwich Publishing Group, Inc.) 2002.

- Victor Gruen 1948 quotation reprinted

- Jeffrey Hardwick, Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2004). p. 101.

- Jerry Jacobs, The Mall: An Attempted Escape from Everyday Life. (Prospect Heights: Waveland Press, Inc., 1984) p. 4.

- ibid.

- Ingrid Pfeiffer, “Circumstantial Evidence: Shops and Display Windows in Photographs by Eug ne Atget, Berenice Abbott and Walker Evans.” A Century of Art and Consumer Culture, Edited by Christoph Gruenberg and Max Hollein (Frankfurt, 2002), p. 93.

- ibid.

- Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Arcades Project. (Cambridge, 1991). p. 92).

- Anton Kaes, “Metropolis: City, Cinema, Modernity.” (Expressionist Utopias: Paradise, Metropolis, Architectural Fantasy, Timothy O. Benson, for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2002).

- Buck-Morss, p. 92, 93.