She had been seeing her therapist for almost seven months before she mentioned the photograph, and even then she brought it up incidentally like it was no big deal. Here’s how she remembers it:

At the bottom of the garden in the house she grew up in was a small shed in which her father kept a stepladder. She retrieved the stepladder, dragged it across the garden, into the house, up the stairs and set it up beneath the loft hatch. She climbed up into the loft and started looking through the stacks of cardboard boxes her father had put up there over the years. She couldn’t find what she was looking for, so she went further into the darkness. At the back she found some boxes she didn’t recognise, opened one and saw a stack of photographs. She carried it across to the hatch and lifted one of the pictures – a Polaroid – into the light. Then, upon seeing the content of the photograph, she instantly dropped it back into the box, closed it up, put it back, climbed out of the loft, returned the stepladder and never spoke of it to anyone.

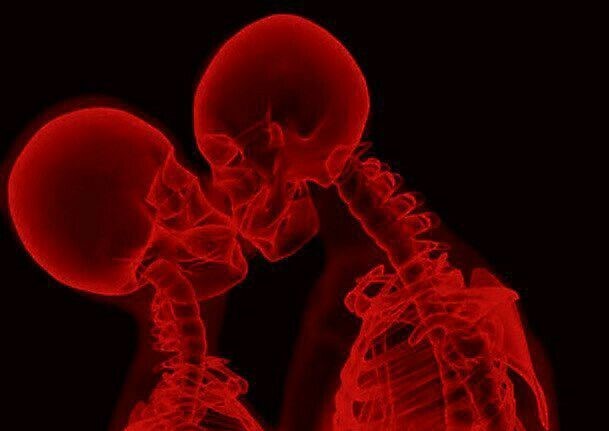

The photograph contained a naked man that she didn’t recognise, and a naked woman that she clearly recognised as her mother. If you want to know the specifics of what they were doing in this photograph I would say in the interests of discretion I can’t describe it, but I would invite you to imagine a similar photograph of yourself that you might plausibly want to keep, but keep hidden.

Her therapist sat quietly in the languorous pose he often adopted, hands resting on his stomach, legs stretched out in front of him.

‘How old were you?’ he said eventually.

‘Maybe fifteen?’ she said.

There was another considered pause. She glanced at the clock, half past the hour, still a good amount of time.

‘Did you tell your mother what you saw?’

‘No.’

‘Have you ever told anyone?’

‘No. Just you.’

Her eyes rested on the plug sockets on the wall, which was where her eyes seemed to rest naturally when she didn’t know where else to look.

‘So how long have you been carrying that around with you?’ he said.

‘I guess about thirty years,’ she said.

They sat quietly, letting the idea of thirty years fill the room.

At first, she had disliked her therapist, even resented him. She wanted him to talk more, to explain things like a doctor might. But he didn’t. He spoke rarely, and – when he did – slowly. She took it as lack of interest, even an absence of care, and more than once she had considered giving up on the endeavour entirely, but she kept coming back. His skill, she came to decide, seemed to be in the way he could, for fifty minutes, make it seem as if the world outside that room had frozen in time. Nobody knew where she went on Mondays after work, and while she was sure that nobody thought of her at all, she liked the thought that if anybody did, they would never think of her sitting in this room, with its old fashioned writing desk and scruffy bookshelves, watercolour landscapes slightly wonky in their frames, two chairs at an oblique angle, clocks positioned where they could always be seen.

‘I think I resented my mum,’ she said.

Her therapist nodded slowly, a nod of acknowledgment rather than agreement.

‘I mean, partially because of what she was doing in the photograph. She was always very discouraging about that kind of thing. But also, because it was a photograph.’

Her therapist waited, recrossed his feet, one over the other, then said, ‘What do you mean?’

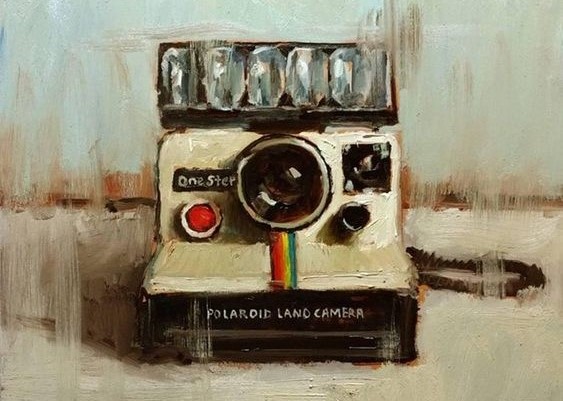

‘Well photography was always my dad’s thing. It was his hobby. Landscapes, still lives, portraits. He had ambitions to do it professionally but it never worked out. He used to set our kitchen up into a makeshift darkroom. Red light, plastic trays of chemicals that I can still smell if I remember them. He’d make test strips where he would expose a little piece of paper in increments, testing for the perfect exposure. He took it really seriously. It’s like she also stole photography from him.’

She didn’t look up from the plug sockets but if she had she might have caught a brief micro-expression of confusion cross her therapist’s face, then disappear.

They sat in another protracted moment of silence. Seven months of therapy and she was starting to get the impression that silence – a kind of controlled, collaborative silence – was one of its most interesting ingredients. At first, those long spaces between their shared sentences left her feeling like she was drowning, but after a while she started to enjoy them. She noticed how much of therapy was conducted in silence, and likewise how much of life was lived in silence, and the lengths most people go to avoid it: cafes with their overloud radios, televisions left on in the background of their homes, the hollow small talk that lets people keep their relationships alive without risking too much of themselves in the process. Not all of her therapy sessions could be said to have contained anything revelatory, but the slowness of them was useful in a different way.

‘So, what do you make of all that?’ she said to her therapist. A daring sort of question she had only recently developed the nerve to ask.

He sat up a little straighter, drew a slow breath. ‘Well,’ he said, giving the question a more serious kind of attention than most people would have. ‘I guess I’m wondering who took the photograph.’

The silence that followed was deeper than most. It’s hard to say what she was thinking about. Maybe she was thinking of that photograph, how small it seemed, how brief the moment it contained had been, how enormous it had grown in her mind. Maybe she was wondering where it was now, or what it would be like to see it again. Maybe it was that special kind of nothingness, that white-noise-TV-static that can fill a busy mind but leave the thinker with no idea what had been thought.

‘A timer?’ she said eventually.

‘What do you mean?’ her therapist said.

‘A timer on the camera to take the picture.’

‘It’s possible,’ he said, with a slight inflection that transformed its meaning from ‘possible’ to ‘unlikely.’

She tried to remember if those old-fashioned Polaroid cameras had timers. She was sure they did.

When the session came to its end, they finished it the same way they always did. She said, ‘Same time next week?’ and he said, ‘If that works for you.’ He led her out of the room to the front door and they said goodbye in their awkwardly formal way, and as she stepped outside, the world seemed to unfreeze and come back to life. She turned on her car, turned off the radio and drove home in silence, trying to pay attention to the changing shape of her thoughts as they passed through her head.