The Home’s western boundary were the tracks of the Liberty Bell Line, a trolley that had operated between Allentown and Philadelphia in the nineteen-forties. It was a single track on a ballast of rubble-filled earth that arched over our creek, a shallow meandering stream which had been re-channelled through a concrete tunnel. By 1956, the track had been abandoned but the ballast, now dense with saplings and brush, found use by the locals as a semi-concealed wooded lane leading to what became a town dump.

Walking south and uphill on this stony ridge, on your right was a bullet-riddled heap of Frigidaires and Whirlpools, tins and bottles and cardboard cases of empty Pennzoil cans which had been heaved at night from the trunks of cars. Wrecks had also been towed up and then sent smashing into other wrecks, long dead Chevys and stripped-out Plymouths. Naturally for us “Home-boy” inmates, anything west of the tracks Sister Superintendent Alfreda had deeply etched on the tablet of NO. You’ll get bitten by a rat and go straight to Hell! Rats, we understood, were in collusion with Satan.

The ballast’s east side was a plunge down to our new fire pond. Some years before, a workman’s torch had set ablaze one of the Home’s original farmstead buildings causing Sister Alfreda to insist on a ready water supply for any future emergency. In winter, when it froze and was therefore declared polio-free, the ice and slope became our winter sled-way. Of the six years that I lived at the Sacred Heart Home and School for Friendless, Crippled and Convalescent Children, one of my fondest memories is the image of a sled-load of screaming kids pushing off from the tracks and hurtling down between the trees with such velocity that when we hit the ice with a thunk, we’d careen sideways until we crashed and spilled from the sudden stop at the far bank.

Entire Saturday afternoons were given to these icy chases, despite having one toboggan and a few Flexible Flyers for over one-hundred kids, which meant that much of the afternoon was spent shivering in a long line on a windy hill just waiting for your turn to fly. Perhaps the nuns thought that the wait and cold would make us stoics, would help us to prepare for a devout life of sacrifice; and thought, too, that some of the older boys were on the brink of teenage angst and rebellion, and energy consuming diversions were necessary to keep the Home’s peace. That is, theologically safe diversions.

Next to the fire pond was our old swimming pond, a placid circular pool that for me was an escape into a sub-aquatic dream. One-half of its bottom was lined with yellow clay. The other, swimming half, was gravelled with a layer of crushed limestone. In summer, depending on the angle of the sun, in the clear shallows the stones reflected a bluish-gray making the pond appear as if a rocky half-moon rested beneath its water. Farther out were the mermaids, thick bundles of submerged grass that undulated with the currents. An afternoon spent peering into this quiet world would show schools of minnows darting in and out among the weeds, crayfish bumping tail-to-tail in the narrow canyons between the stones. Life below was snug and silent, the waving of the weeds hypnotic, and the old pond could be explored until the sun dropped behind the trolley tracks. I don’t recall when first becoming fascinated with the pond’s flora and fauna. But in time came to rely on it as a refuge from the Home’s constant noise and chaos, its regimentation and practice of mass discipline.

This marshy, pre-Cambrian fertile ground was also a place where insects proliferated by the millions: clouds of marsh flies, cruising wicked horse flies, dragonflies, partnering blue damsel flies, black and brown crickets, yellow mud-digger wasps, and thousands of inch-long threads of larvae sucking air at the water’s edge which would metamorphose into hordes of mosquitos. By late spring the pond was in full spawn and tadpole bloom, and snappers and native reptiles fattened up on this easy prey all summer long.

If a stray beagle sent the nuns into a panic, since all dogs were carriers of disease and death and were forbidden anywhere on the grounds, then snakes were a swooning terror, their fangs only incidental to their incomparable powers of evil. You could ask anyone, because in first grade Sister Hademunda had chalked a picture of an asp with horns so we wouldn’t be fooled. Boas and vipers were devils in disguise, she said, intentionally loosed upon the earth by the Evil One. To tempt. To deceive. To subvert the innocent be you asleep, awake, in church at prayer or, typically on an August afternoon, be you and twenty idle others on the playground languishing through another round of pitch-and-hit.

The depth of this terror was shown one day when a kid at bat saw a green garter glide over home plate. A harmless, pencil-thin juvenile that quickly put an end to our boredom as we rushed to watch it slither under the tracks and coil around the axle of one of the wrecks.

It didn’t occur to us to just marvel at this natural wonder, to then return to our sponge-ball and stick and the nuns would have never known what beast had breached their realm. But as if our curiosity, and supposed learned generosity, towards nature had reached an unforeseen limit, we came under a spell and stormed it with rocks and bottles, as if one moment we had been in an indolent stupor and were now crazed from too much light and August heat. We became an armed guerrilla patrol without adult supervision, oblivious to the knowledge that our revolution’s demise was foretold at the first crack of a Coke bottle against the windshield of a rusting Plymouth, that upon hearing the first pops and tinkling sprays of glass, the nuns had already out-flanked us and had plans for retaliation.

Sister Ernelda shouted alarm. In a minute we were corralled into a tight group under the blazing sun. Sister Hademunda led off with a decade of Hail Marys. We knelt and dutifully followed her lead, and cooked and sweated as the mumbled penances rolled off our tongues. Fortunately for us, Ernelda and Hademunda too baked in the heat, and it wasn’t long before order was deemed restored, piety re-affirmed, and they released us.

All was well until later when Mr. Paul, seated high on his Farmall and mowing the tall grass around the ponds, by chance cast his eyes downward to notice a bloody segment of another reptile sliced up in the blades of his sickle bar—and had he not witnessed our punishment an hour before, finding a half-dead reptile would have probably remained uninteresting. Just another sign of animal fecundity in the dog days of summer.

Mr. Paul was generally a speechless and imperturbable man. One never saw him riled or irritated with our questions, and neither, from what we could see, was he given to teasing or antagonizing the nuns, who were obviously his employers. But as he reached into the stubble, it so happened that day, lizard hot and dry as it was, he must have had something else in mind.

Often he enjoyed sharing with us discoveries he had made while doing his chores. One winter it was an eyeless, desiccated owl he had found in the rafters of the old barn. Another time we followed him to his tool shed where he raked back a layer of leaves revealing a litter of blind, new-born mice, the runts squirming like pink sausages in the cold air.

A dozen leaky faucets, a half-dozen clogged toilets, a week’s worth of ladders and light bulbs, his was a life of a million fix-it projects, and as the sole resident fix-it man who seemed never to be in a hurry, perhaps he thought he had a million years to fix it all.

Like us, he knew the Home’s List of Forbiddens: Climbing trees—You’ll fall and break your neck! Exploring the creek’s cavernous tunnel under the tracks—Something will grab you and eat you! Especially the forbiddens that the nuns saw as approaching the criminal: Wandering too far up the trolley tracks—You’ll get lost and die of starvation! The worst was hopping the fence for a stroll along Coopersburg’s Main Street. Such perpetrators were summoned before Alfreda where you’d be slapped until your cheeks pulsed with a red numbness. And slapped again for daring to soil your pants in her presence. The reproach wasn’t because you’d be kidnapped for ransom or found murdered in a corn crib. It was because, she warned, You’ll get hit in the street by a machine! Confined by these, Mr. Paul seemed sympathetic to our quashed desire for wonders, natural and otherwise. For something new. Or at least for something that came from beyond the Home’s four walls, since Life and Look magazines, newspapers and radios were off limits to us.

Stocky, muscular, in his early forties with a blue heart tattooed on his left bicept, he advanced whistling a tune while holding one hand firmly behind his back. When he smiled and paused mid-way, we took the cue and raced around him. Slowly, he brought forward the glistening, golden-green head of a snake, its eyes half-closed as if sleeping in the palm of his hand. “Ever seen one of these?” He raised it level with our eyes. “Watch,” he said, and poked it with his finger making its jaw open and twitch. “Snakes got more lives than a cat,” he said. “Some say they live forever ’cause they shed their skin.” He marked our amazement, then lowered his voice. “They got something else, too,” he said. “Snakes got magic.” We huddled closer, his voice now almost a whisper. “F’r instance, if you stick it under your pillow and make a wish …”

The words exploded in our ears. Magic. Pillow. Wish. A hand flashed out and snatched it, then bolted for the dormitory with the pack of us stampeding after him. We crossed the playground, dashed across Linden Street and charged up the stairs to the Small Boys’ dormitory, unaware that the nuns had seen and were already on Mr. Paul.

They caught us in the dorm, we on one side of our cots and they standing in a rigid line opposite. Sister Mary Gumara untied her kitchen apron and spread it on the floor, jabbing her finger downward demanding our contraband. When nothing dropped, she issued threats of pain and torture at the hands of Father Emerich. Yet for once we appeared deaf to these. Of course the words defiance and revolt hadn’t even entered our minds, and surely none of us could have phrased exactly what was in our minds. But we stood with our mouths shut and our bodies frozen, our eyes glued to their contorted faces.

The passing minutes only confirm for us the validity of Mr. Paul’s words. Moreover, we contrived to believe what we wanted about our treasure: that it was a lucky charm that could grant wish after wish when placed under a pillow. That it would work for anyone, night after night. That it was a golden sac of skin packed with fortune, a heavy, compact body oozing a kind of magic that was limited only by our five- and six-year-old imaginations, which now seemed suddenly free from the Home’s mission of constant indoctrination.

The nuns re-grouped into a wedge behind Sister Gumara, blocking the doors. In the lengthening silence, fearing reprisals some of us retreated to the windows when a slamming door and steady footsteps began to echo up the stairway. The nuns parted as Superintendent Alfreda entered the room. In a subdued voice she questioned Ernelda, while searching our eyes and surveying the room over Ernelda’s shoulder. She then turned to Gumara. “Reclaim your property, Sister.” Gumara grasped the apron and re-tied it around her waist. Alfreda studied our faces, taking time to absorb each of us one by one. Finally she pointed to the door, “Double file and everyone out!”

We clamored into lines, our familiar older ones first, smallest, younger ones last. Alfreda’s arm shot up, and we shuffled like a docile herd, her figure fixed before the doors forcing us to split around her as if she was a tall rock in a field.

The nuns escorted us back to the playground where, without a word and to our surprise, we were dismissed and they promptly took their leave. They had loads of bedsheets to soak and wring and hang up to dry; crates of donated sweet corn to shuck, sacks of potatoes to scrub and boil for the day’s meal. When no reprimands came at suppertime, we came under the illusion of a lucky truce, assuring ourselves of victory and duly credited our new found charm. After bedtime prayers, we genuflected and scampered into our small cots. Pulled our sheets to our chins and waited for a night filled with dreams. For scooters and Schwinns. Popsicles for a hot summer day.

![]()

Luck.

A word we all knew even if we didn’t.

Had we ourselves been lucky or had come from lucky parents, how many of us would have arrived as a Sunday night bundle left on a convent’s doorstep? A Monday morning drop-off announced by a doorbell and a car speeding off on Route 309?

Invention and Contrivance.

Words we also knew even if we didn’t.

Sacred Heart was governed by expediency. Rules, mostly, based on fear. The dictate about dogs. Lying and stealing supposedly pre-empted by the fear of having your tongue and hands boiled in a pot Emerich kept in his cellar.

Other teachings meant to ensure faith through shame. Our underwear was a defense against depraved bodily knowledge, a white shield of purity, since it was a sin to look at yourself while peeing. We showered in our underwear, alone in green-tiled booths. At the end of our soaping and rinsing, a hand poked over the door to exchanged our wet-soggy for fresh-dry. Our bodies, we knew, were not ourselves. Our skins being mere vessels for theology.

Our minds, too, belonged to a cosmic other.

Original Sin confirmed that we were dirty inside, and that only your soul was truly yours, that little secret milk bottle inside you that needed lifelong cleansing and filling with grace. Our Wednesday-Saturday showering ritual now reminds me of Mr. Paul’s habitual whistling tune. “Just Walkin’ in the Rain” was his work-a-day favorite as he scraped and painted and did his chores. A song composed by two convicts doing time in a Tennessee prison.

![]()

The luck lasted until that Sunday’s benediction, an all-afternoon round of prayers for the sick, the hungry, and against hurricanes and droughts. At the close of our missals, we were called to muster at the foot of our beds. Alfreda stood in the center of the room, flanked by Afra, Gumara, Thecla, Itwara, Ernelda, and led off with an Our Father. The nuns followed and finished with a loud, determined Amen, then began ransacking the dorm. Sheets and pillow cases were stripped and tossed in a heap. Mattresses rolled up and dragged to a corner. On command we emptied our pockets sending streams of marbles clacking and racing across the floor. Windows banged open and banged shut. Our iron cots screeched across the tile to lay bare the floor beneath them, then jammed in a pile against the wall. The shock of steel against steel made us jump. Made some of us cry and whimper. Made all of us cower and cringe.

Shock turned to anger when our private boxes were dumped like trash, their contents raked and kicked through. Each of us had an assigned wooden box for personal belongings, a misnomer because, if for a trinket or two, none of us had any belongings. Not really. Maybe you saved a tangle of string because you never knew when you might need a lace for a shoe. Mittens because the wool was still thick and free of holes. A quartz “gem” found on the playground. Essentially though, if you had nothing, you owned nothing. Yet we all had one thing to keep safe and secret. And if it wasn’t stashed under your pillow it was stored on a high shelf above a bent rod of mothballed coats and scarves.

We saw the nuns’ action not as a violation for how they treated our things. But as a disavowal of a singular trust and privilege, the tacit agreement between us and the Home: that though you as a person belonged to them, what you safely put away was supposedly your own. Some thing, you thought, for whatever reason, only you would have saved. It was our one individual allowance—a hollow, plywood cube with a white number stenciled on the side. In mine was a hand-sized cardboard box of crayons so worn to stubs that no one else wanted them. Cached for their waxy aromas, and prized as my musical kaleidoscope, delighted by the chorus of sound it made when I held it close and tumbled it against my ear.

![]()

The chaos passed into the six o’clock supper hour, and still finding nothing, Alfreda returned the nuns to their ordinary Sunday duties. Sister Itwara, our dorm mother, was left to oversee the room’s re-coherence of cots and mattresses, one pillow to one white sheet to one gray blanket. Our cubes re-shelved, their heaped contents to be sorted and reclaimed later. By nightfall, Itwara bumped and knocked a wide long-handled broom through the aisle that separated our twenty-four beds, the broom used to measure-off the foot rails into two perfectly aligned rows of apostolic twelve.

It wasn’t until the late dark hours that our charm was at last discovered, its odorous magic exuding from a window sill until someone finally tossed it down the laundry chute. Come morning, Monday washday, the Home awoke to an horrific female scream.

Which reaction incited another.

The pine plank spiked to the ground that served as our home plate was declared ‘stained,’ and Mr. Paul, with Sister Alfreda attending nearby, was ordered to pry it up with a crowbar. Alfreda then slipped from under her arm a flattened cornflakes box and called for someone to find a rock while the rest of us, idly kicking at the hard-packed soil, watched as Mr. Paul loaded his tools, mopped his brow, hunched over his wheelbarrow and pushed off from the field.

Notes:

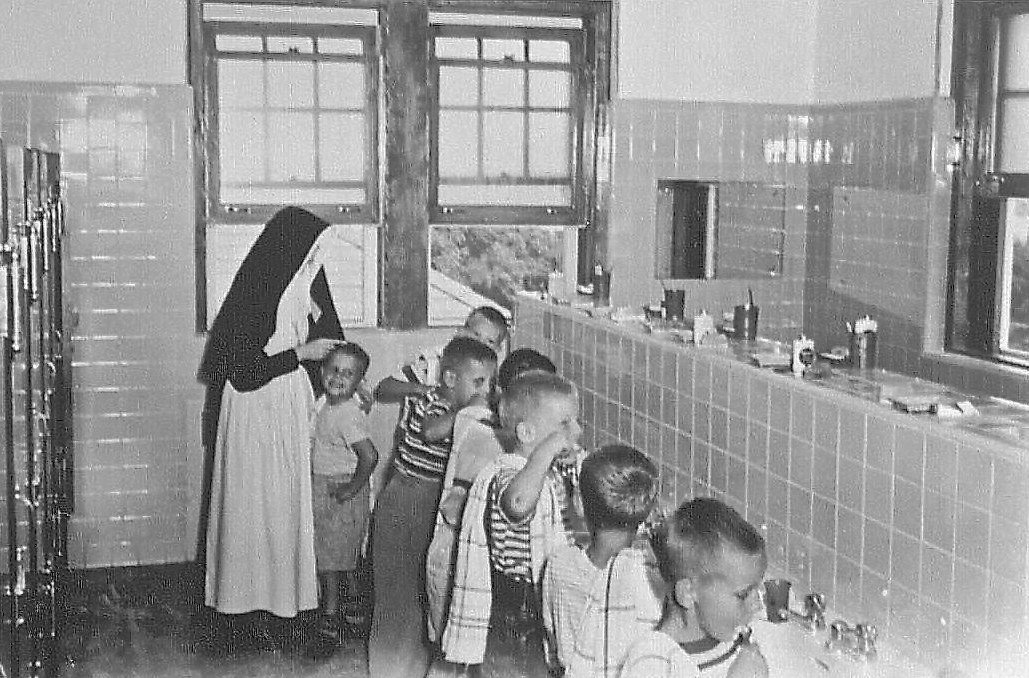

Photograph: Small Boys’ Lavatory. August, 1952. Sacred Heart Home and School for Friendless, Crippled and Convalescent Children, Coopersburg, Pa. Courtesy Missionarii Sacratissimi Cordis. Used by permission.

Pennsylvania’s Liberty Bell Line ended service September, 1951.

“Just Walkin’ in the Rain” was written in 1952 by John Bragg and Robert Riley, two inmates at Nashville’s Tennessee State Prison. Song made popular by Johnnie Ray, in 1956.