The Most Bitchin’ Brontë: Unleashed Animus in Wuthering Heights

Feminist readings of 19th Century British literature are complicated by the fact that the rising awareness of certain issues like cruelty to animals and the mistreatment of children—issues that have always cleaved to feminist theory—challenge social and legal realities at their ideological foundations. The fact that gender relations operate within a hierarchy dictates that one cannot question the place of a single element in that ordered set without upsetting the relative status of the others. To complicate matters, social hierarchies always exist as dynamic spectra rather than as static dichotomies; in addition to gender, one’s position in the social milieu of Victorian England was determined by age, ethnic background, ability (versus disability), and socioeconomic status, to name just a few confounding variables. 19th Century scientific advancements introduced animals to this organization, challenging artists, intellectuals and activists to grapple with where these beings fit in the hierarchical scheme.

The Victorian marriage plot—a narrative structure that serves as the foundation for a large portion of 19th Century British literature—deals with stories that hinge on a protagonist faced with difficult choices concerning his or her selection of mate. This deceptively simple conflict roots the Victorian novel in the aforementioned problems of social status; the protagonist’s decision is not simply a personal choice but a life-changing turning point bearing the full weight of pressures dictating propriety in both public and private spheres. In novels that utilize the marriage plot, social commentary is implicit. Undoubtedly many authors consciously desired their characters to serve as models to reinforce or refute social realities, but even in the absence of such motives, the marriage plot itself serves as an insightful glimpse into history—the writer and her work both being products of their times. Moreover, the expectations of Victorian critics and the general readership of the era demanded stories that not only entertained, but did so within certain moral conventions.

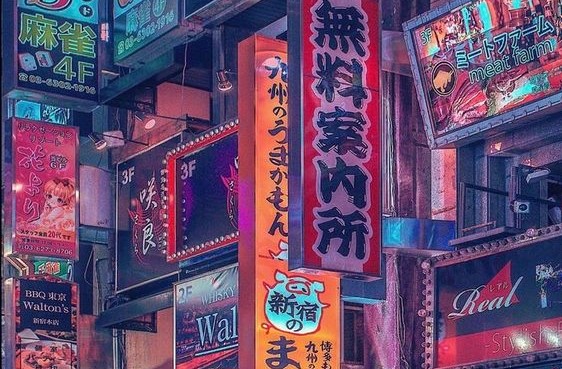

Critics of Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights—a novel that at first glance might seem the perfect image of the marriage plot, initially introducing unsatisfactory marital arrangements and then resolving them into a socially acceptable pairing—attacked the work as falling outside a Victorian aesthetic, driven by a sense of morality that reviewers fail to explicitly define. Attempts to elucidate the novel’s shortcomings suggested that its portrayals of savagery and gratuitous passion were not “permissible” in the novel-as-art. In painting, writes one critic, it is “permissible” to faithfully depict subjects that are disagreeable in a single unredeemed aspect; novel writers are not allowed the same strategy (Britannia NP). The same critic elaborates that certain “scenes of savage nature” that may be pleasing in reality (or even in visual art) have no place in the purposeful art of the novel (Britannia NP). Another critic questions the plausibility of the main character: Brontë’s choice to render Heathcliff as dominated by the single aspect of cruelty is “inconsistent with the romantic love that he is stated to have felt for Catherine Earnshaw” (Examiner NP). Finally, Brontë’s language in and of itself comes under fire: “It may be well also to be sparing of certain oaths and phrases, which do not materially contribute to any character, and are by no means to be reckoned among the evidences of a writer’s genius” (Examiner NP). The peculiar complaints of the critics of Wuthering Heights—along with evidence of the author’s own personal stake in her work in terms of both biographical reference and probable social views—make this novel a useful platform for the discussion of the voice of the Victorian female writer in her literature. Whether or not Brontë consciously aimed to champion women, it is indisputable that her work rejected certain critical notions of the aesthetic as linked to morality and appropriated imagery considered impermissible in the female realm. Revisiting Wuthering Heights in terms of authorial voice and animal symbolism allows for a feminist reading that likens Brontë’s methods to the reclaiming of the language of one’s oppressors—a phenomenon that continues to this day.

In literature, “voice” embodies a difficult blend of detached technique and unconscious habit. The writer is literally putting words in her characters’ mouths, but this language is all originating at the same source—and the author herself is a product of society, no matter how strong her intent may be to question the social order. The critical response to Wuthering Heights sets the author’s relationship to her language in relief on yet another level: the tension between accurately representing a character through his speech, and censoring that character to render a novel “permissible” for the general readership, creates a conflict important to literature of this period. This point of conflict is closely associated with the role of animals in Victorian literature in general, and in Brontë’s Wuthering Heights specifically. Growing social movements for the prevention of cruelty to animals generated a new literature of activism; use of the media made public discourse common and accessible, simultaneously raising awareness of issues and, paradoxically, rendering the population accustomed to scenes of cruelty. Before examining this paradox, however, it is necessary to discuss a more subtle facet of the confluence of language, literature, culture, and cruelty: the insult.

Modern readers of Victorian literature soon become familiar with conventions of omission and euphemism: sexual congress is implied and blasphemy is partially rendered, with dashes serving to curtail the full verbal reality of the curse. Interestingly, Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights fully embraces these conventions, raising questions about what “oaths” might have elicited the negative critical response presented above. Kate E. Brown offers that ability to curse—and, by extension, to insult—defines the voice beyond cultural fluency, inhabiting the body and expressing concepts in a modality that “hovers between the literal and the metaphorical” (539). This conceptualization of “voice” forges an essential link between speech and symbol; by writing a thing one actually conjures it. Critics sensitive to such notions might reasonably be assumed to extend this “word made flesh” phenomenon past the characters and their fictional voices to place the responsibility for “permissible” language on the author. In the religiously imbued patriarchy of Victorian England, this kind of judgment, whether conscious or unconscious, would explain negative critical responses to Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights. Even if a Victorian critic were to read Part Two of Wuthering Heights as a moralizing resolution to the inversions and backward behavior of Heathcliff and Catherine Earnshaw in the primary marriage sequence, the “depravity” of the explicit and implicit insult behavior visible throughout the story would render the language of the novel immoral in and of itself. Likewise, in terms of sexual insult, one must consider the fact that the cultural construct of offensiveness can operate in the reverse, allowing acts to function as vocalized statements. Flynn notes that non-conformist sexual behavior operates as an insult not only to the perpetrator but also to the observer (4-5). This further explains the discomfort contemporary readers of Wuthering Heights might have felt in seeing young Catherine traipsing about the moors or saucily rebuking her protectors. At one point she even tosses her bible into the dog-kennel—an action with a subtext of insult that will become more and more apparent as the human-animal relationship is examined further. The idea of insult by association is essential to some aspects of the animal’s role in literature; the likening of humans to animals encompasses both the literary technique of imagistic analogy and the cultural association of individuals to beings that represent positive or negative qualities.

As animals were utilized more and more frequently as characters in literature, verbal or associative insults linking humans to negative qualities of beastliness prevailed. The uncomfortable association of humans with animals has deep roots in the tradition of English language insults. According to The Oxford English Dictionary, the word “bitch”—meaning literally “the female of the dog” (“Bitch,” Def. 1a)—has been used as a gendered insult since circa 1400. The OED differentiates the insult from the scientific term thusly:

Applied opprobriously to a woman; strictly, a lewd or sensual woman. Not now in decent use; but formerly common in literature. In mod. use, esp. a malicious or treacherous woman; of things: something outstandingly difficult or unpleasant (“Bitch,” Def. 2a).

“Bitch” as an insult to women, applies the image of the female dog in heat to berate feminine behavior considered sexually inappropriate, further reinforcing Flynn’s notion of social conduct serving as insult. The “dog-like” female was especially displeasing to the Victorian sentiment. In A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue, Francis Grose defines the term “bitch” as follows:

BITCH, a she dog, or dogess ; the most offensive appellation that can be given to an English woman, even more provoking than that of whore, as may be gathered from the regular Billinsgate or St. Giles’s answers, “I may be a whore, but can’t be a bitch. ”

TO BITCH, to yield, or give up an attempt through fear ; to stand bitch, to make tea, or do the honours of the tea table, or performing a female part. Bitch there standing for woman, species for genus. (13)

Grose published his Dictionary in 1785. The understanding that the word “bitch” was enough in use in Victorian England to warrant its singling out as a particularly abusive appellation for women should red-flag the association of women and dogs in literature—even in absence of the explicit use of the word “bitch” as a vocalized insult. The potential power of such associations is strengthened even further when one remembers critical pressure to operate via euphemism and conventional omissions for the sake of linguistic propriety. Euphemisms serve society by allowing for a generally accepted decorum to be maintained even in spite of difficult topics of discourse. The act of name-calling serves the sociological purpose of putting a person in his or her place. If gender is built into the structure of society, then both euphemism and insult become essential for the security of the social order. The inextricable relationship between social structures and language makes literature a lens through which one might examine social contexts—through characterization and narrative decisions, but also in terms of how language is used. In fact, authorial intent must at times be read against the language, with attention to both what is stated and what is omitted.

The tension between the explicit and the implicit is central to a contemporary feminist reading of Wuthering Heights. This tension also reflects certain qualities of the relationship between animal rights literature and popular literature in Victorian England—a relationship that becomes crucial to how animal characters drive narratives. According to Harriet Ritvo, “Any scientific expression requires literary as well as technical explication; it must be interpreted in the linguistic and cultural context to which the author belonged” (“Our Animal Cousins” 49, “Science as literature” 137-138). The plight of animals in 19th Century England was communicated to the public through literature that aimed to raise awareness about moral issues concerning cruelty to animals as entertainment and through texts describing the horrors of the scientific use of vivisection. These texts used the same kind of artful and accessible language popularized by the novel to create narratives of animal cruelty. In discussing an exemplary piece of anti-vivisectionist literature, Kreilkamp writes, “In these animal narratives—melodramas of beset animality—readerly subjectivity and middle-class ‘humanity’ are defined according to the logic of cruelty and sympathetic witness that requires a suffering creature” (106). Though Kreilkamp is commenting on a periodical article, the narrative structure he invokes is indistinguishable from those employed in works like Brontë’s Wuthering Heights.

The narrative structure that requires a suffering animal develops characters by exposing a villain and allowing the reader to make judgments of lookers-on. New considerations of animals as worthy of protection allowed creatures to stand in as a trial for both fictional characters and their readers; in Wuthering Heights, for example, the reader encounters several instances of wanton cruelty that if gratuitous on the part of the perpetrator offer a more complex judgment of those who witness it. As noted above, critics took exception to Heathcliff’s cruelty, which has been regarded by some as too uni-dimensional. Consider, however, Heathcliff’s hanging of Isabella’s lap-dog. Heathcliff does this for no express reason save to torture his new wife. However, Isabella’s passivity says something about the inefficacy—or, perhaps, even cruelty—of her character. Adams describes this scene as operating on many levels. First, it associates cruelty to animals to domestic violence; as we will see later, among the many functions animals serve in Victorian literature is that of a stand-in victim for crimes too graphic to be “permissible” in genteel literature. In this case, Heathcliff’s hanging of Fanny the lap-dog announces the impending doom of the union and directly links spousal abuse to animal cruelty (2). This scene also nods to the complexity of human-animal relationships and their traditional link to feminist readings; it would be overly simplistic to call this scene a demarcation of abuser and victim. The narrative of animal cruelty actually renders the dog the only true victim; Isabella remains open to the reader’s judgment. Furthermore, the absolute helplessness of the dog who remains loyal to Isabella calls attention to a kind of passivity that warns against being a willing victim. Writes Adams, “If we look at the victim, the dog Fanny, we are struck by the disgust she provokes because she remains loyal to a mistress who has abandoned her (2). Heathcliff further ties together languages of science and abuse, sealing the connection between Isabella and the image of the abused or exploited animal while underscoring her complicity: “‘…I’ve sometimes relented, from pure lack of invention, in my experiments on what she could endure, and still creep shamefully cringing back!’” (Brontë 133).

The comparisons prompted by the inclusion of animals in novels are troublesome. Popular animal rights literature portrayed humans and animals in reversed positions—with animals dressed in clothing and humans suffering from bondage or other threats—in order to generate sympathy. Flegel, however, suggests that such renderings actually betray the complexity of such comparisons, noting that the comparisons functioned to actually deepen some of the pejorative associations between types of animals and different genders and social classes (247-252). The actual depiction of animal suffering created spectacle ostensibly to utilize absurdity for enlightenment against cruelty, but the “moral” of the representations could only be communicated in a society where a context of abuse of creatures for pleasure or profit was already accepted.

Animals could function as “characters” both in propaganda and according to the moral expectation of Victorian literary critics because society was accustomed not only to categorization but also to ranking. According to Ritvo, “Well-bred horses and dogs were frequently compared favorably with human types categorized as ‘primitive,’ on grounds of intellect, as well as of disposition and personal appearance.” (“Our Animal Cousins” 50). Just as social rank depended on factors such as wealth and ethnic background, “breeding” determined how an animal fitted into its narrative relative to humans. The entire hierarchy of sentient beings hinges on power. Derrida identifies a “carnivorous virility;” the Victorian society Abraham identifies as patriarchal—like most Western society—has not only relegated some types of killing to the ranks of non-murder, it has also identified the slaughter of animals (in some cases) to the level of a power-play (Abraham 93, Kreilkamp 91-92). To understand the roles of animals in Victorian narratives one must remember that different types of animals rated different rank; not all beasts could earn the rank of “pet” (Flegel 252-254). Kreilkamp identifies the difficulties of reconsidering rank as the “other” social history that ran parallel to changes in legislation. Within this “other history” of nineteenth-century animals and animality, questions of evolution and genetic linkage are subordinated to those of cruelty and sympathy, the spectacle of suffering, and the definition of the “human” as an ethical, rather than biological, category (Kreilkamp 91).

The “disposition and personal appearance” of creatures played directly into the Victorian sense of hierarchy. The importance of such qualities further elucidates how being “dog-like”—when the likeness in question concerns undesirable qualities of disposition or appearance—would define “bitch” as a most odious term (Grose 13, “Our Animal Cousins” 50). Furthermore, such considerations are essential in identifying how social status, cruelty, law, and morality all dovetail in the discussion of both animals as literal beasts and as symbols in dialogues of degradation or activism. The Victorian age saw a glorification of the middle-class. The aforementioned paradox of propaganda serving to prime the public for the very scenes it hoped to prevent had another important if more subtle facet; the increasing taste for the separation of public and private life was being undermined, in a way, by legislation that sought to protect women and children in the domestic sphere. Furthermore, the concept of the patriotic English identity was bound in an ideal of manly sportsmanship tied to certain pastimes such as fox-hunting, sparking public debate between ideals of manliness as righteous in upholding laws of protection and more traditional views emphasizing strength and virility. These debates related directly to literature, challenging writers to reconsider their male heroes. Writers like Anthony Trollope—who, it should be noted, generated a significant amount of literature that critically examined Victorian marriage conventions—found themselves at odds with notions of cruelty that desired a reassessment of “manliness” (Boddice 2, 4, 8).

Emily Brontë left—through her writing and by example—ample evidence that she gave in-depth thought to the relationship between humans and animals, the nature of cruelty, and the idea of abuse. In an essay on animal cruelty composed during her time as a governess in Belgium, Brontë shares a colorful anecdote:

“But,” says some delicate lady, who has murdered a half-dozen lapdogs through pure affection, “the cat is such a cruel beast, he is not content to kill his prey, he torments it before its death; you cannot make this accusation against us.” More or less, Madame . . . You yourself avoid a bloody spectacle because it wounds your weak nerves. But I have seen you embrace your child in transports, when he came to show you a beautiful butterfly crushed between his cruel little fingers; and at that moment, I really wanted to have a cat, with the tail of a half-devoured rat hanging from its mouth, to present as the image, the true copy, of your angel (Kreilcamp 96).

It is notable that Brontë’s illustration of the gentlewoman’s hypocrisy cannot rest on pure external judgment, but rather requires an example drawn to a “natural” dynamic of cruelty between the cat and mouse. This observation raises some troubling questions: Do we as humans “accuse” the cat for attacking its natural prey? If not, must we recognize some part of the young boy’s nature that dictates he use of his superiority over butterflies to abusive ends? Most disturbing, if there exist “natural” power hierarchies, and if such hierarchies naturally instigate abuse, must women fall into this hierarchy as victims that might be protected—humanized—but never truly empowered? Kreilkamp suggests that the tone of Emily’s anecdote betrays a delight in the natural drama played out between cat and mouse—a reveling in bestial passions that would definitely explain certain narrative choices and themes in Wuthering Heights (96). And yet this delight must also elicit questions about whether or not Brontë can be said to have rejected the exercise of violent power absolutely, or whether it must be assumed that she accepted brutish acts when carried out according to her concept of a natural order. If we accept the latter assumption, the feminist strength of Brontë’s work lies not in her rejection of “male” violence per se but in her insistence that women, too, might exercise such force.

The passage above brings up another subtlety, exposing the dimension of propriety and appearance as a factor in what may or may not be labeled “cruelty.” It seems that the “disposition and personal appearance” of women was challenged less directly than that of men in terms of redefining the ideal. In her essay, Brontë does not explicitly take issue with the notion of being “ladylike”—and yet the suggestion of hypocrisy is enough to have the reader questioning the merit of the Victorian genteel veneer. While Victorian marriage plots frequently expose double standards between men and women, suggest the existence of hidden abuse, and criticize inadequate legal protection of women, few, it seems, actually question conventions about the disposition and personal appearance of women. It is perhaps in this capacity that we might move toward a new feminist reading of Wuthering Heights, identifying Emily Brontë’s conscious or unconscious refusal to offer her reading public the character of a “permissible” Victorian woman—in her own life or on the pages of her novel. Within Emily Brontë’s problematic hierarchy of humanity lie clues for how her controversial novel may be seen as “reclaiming” the language of rebellion, eschewing conventions to attempt to contrive a vocabulary of protest in a language that lacked proper terminology.

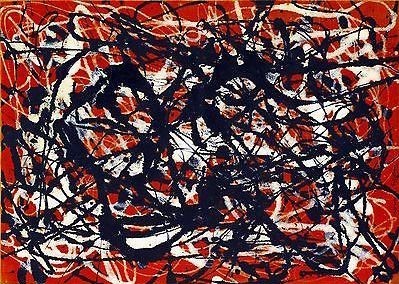

Perhaps the most general observation one might make about Wuthering Heights is that it questions boundaries. Countless critics have read the text as an uncomfortable proximity between nature and civilization, man and woman, brother and sister, and freedom and captivity (Crouse 179-181). However, little has been done to link the very act of muddling such distinctions to the language of scandal. The cultural construction of the insult and the complicated climate of rights protection provide the context for appreciating the immensity of the taboos offered by Emily Brontë. In Wuthering Heights, the common use of symbolism is pushed to the breaking point; instances of humans reduced to animality far outweigh examples of scenes in which the elevation of an animal elucidates the humanity of Brontë’s characters. Kennard offers that Brontë’s “doubling” of Catherine and Heathcliff through their unhealthy sympathy and identification may in fact represent Brontë’s own struggles with her sexuality (23-24). Her argument makes claims that go beyond the scope of this discussion, but Kennard’s speculations on common readings of Heathcliff’s masculinity are incredibly useful to a discussion of the text in terms of gender, insult, and cruelty. Kennard’s theory that Heathcliff represents not simply the “male” Catherine but rather the aspect of feminine rage, leads the way for readings of the flawed population of Wuthering Heights within gender. To clarify, one might directly compare Emily Brontë to both Catherine and Heathcliff, thus parsing the novel’s complex symbolism rather than navigating it according to its deceptively simple plot.

The most striking concrete link between Wuthering Heights and Emily Brontë’s actual life can be seen in comparing details of Brontë’s relationship with her dog, Keeper, and the scene in Wuthering Heights where Catherine Earnshaw is attacked by the Linton’s dog, Skulker. In its entirety, the scene in Brontë’s novel first lays out a picture of the “indoor dog”—a proper lap-dog suffering abuse at the hands of its civilized human caretakers—and then develops the “outdoor” scene, where uncivilized Catherine and Heathcliff encounter the Linton’s more brutish “pet.” Taken together, these elements of narrative assemble a picture of the hierarchy of symbolic animal and human relationships in Wuthering Heights. Catherine and Heathcliff gaze into the parlor of Thrushcross Grange, marveling at the behavior of Isabella and Edgar Linton:

“Isabella…lay screaming at the farther end of the room, shrieking as if witches were running red-hot needles into her. Edgar stood on the hearth weeping silently, and in the middle of the table sat a little dog, shaking its paw and yelping; which, from their mutual accusations, we understood they had nearly pulled in two between them. The idiots! That was their pleasure! to quarrel who should hold a heap of warm hair, and each begin to cry because both, after struggling to get it, refused to take it. We laughed outright at the petted things; we did despise them!” (Brontë 42).

The Linton children are themselves described as “howling.” The human-animal society becomes more complex when in response to hearing Catherine and Heathcliff outside the window the Linton’s release the bull-dog, Skulker, on the children. In a single scene the reader is introduced not only to the suffering of a dog as a result of inhumane—or perhaps even inhuman—treatment, but also the notion that different dogs serve different purposes. While the passive lap-dog is described as a “heap of warm hair”—a decidedly passive and unthreatening animal—the bull-dog is a graphically detailed and explicitly male character: “They have let the bull-dog loose, and he holds me!” (Brontë 42, emphasis added). Catherine is described as Skulker’s “game” (Brontë 43).

Though all the children are likened to beasts—the Lintons with their “howling,” and Catherine as “game”—Heathcliff is ultimately insulted by being likened to a dog in the most extreme sense. “Frightful thing!” cries Isabella Linton (Brontë 43). “Put him in the cellar, papa. He’s exactly like the son of the fortune-teller that stole my tame pheasant.” (Brontë 43). Heathcliff is given the dog’s symbolic role of scapegoat when the Lintons blame the “culpable carelessness in her brother” for Catherine’s injury by Skulker (Brontë 44). The traditional role of the dog as the scapegoat is enacted here; the Lintons themselves had set their dog on its “game,” but they somehow displace guilt to the dehumanized child Heathcliff. The bull-dog, meanwhile, is excused; Skulker is allowed to join Catherine near the hearth. The social hierarchy has firmly arranged itself with Heathcliff below the dogs.

Pairing the observation that all of the “pet children” in this scene are bestialized to an extent and reflecting on Kennard’s speculation that Heathcliff needn’t represent any literal “male” to Catherine’s femininity, one begins to see both the complex problems of Brontë’s social hierarchies and a curious attribute of dogs as symbols in Wuthering Heights. Arguably, none of the Earnshaws or Lintons succeeds in following the societal rules dictated by their sex. The notion that Heathcliff represents rage rather than essentially masculine cruelty complements the aspect of his character that is undeniably a victim. Conversely, Catherine’s utter lack of sympathy and startling courage could be construed either as inappropriate exaggerations of feminine reserve or as character traits tending toward the masculine. Edgar Linton is consistently referred to as effeminate, and Isabella (as we have seen above) demonstrates first a repulsive passivity and then what might be considered a too-rash faithlessness in finally leaving her husband. Again and again the reader is forced to vacillate between seeing the conflicts in Wuthering Heights as arising from violently opposing dichotomies or inadequate attempts at integration. If one expands Kennard’s arguments one might begin to see these inter-character conflicts as manifestations of Emily Brontë’s turmoil-ridden exploration of her own identity—sexually, as suggested by Kennard, or more generally as a woman reclaiming passion, violence, and the strength to assert as human rather than gendered realities.

Kennard’s reading of Wuthering Heights as a lesbian text offers that Heathcliff is not a man but a kind of superwoman—a representation of feminine rage stemming from Brontë’s repressed homosexuality. Emily Brontë and her sisters were not only aware of social issues that tied to animal and human rights, they were also educated enough in contemporary literature to be exposed to English and French authors who were beginning to deal more explicitly with alternative sexual narratives (Gaskell 22-23, Kennard 17-21). If Kennard’s thoughts on Brontë’s personal conflict do in fact have merit, I offer that it is more likely that such conscious or unconscious turmoil affected all of Brontë’s attempts to render gendered individuals; rather than seeing Heathcliff as the lone symbolic character within a more standard cast, one might read the cast of Wuthering Heights as Emily Brontë’s greater project of working out gender on her own terms.

Accounts of Emily Brontë’s life paint the writer as an interesting (or even odd) character who defied certain Victorian notions of femininity. In her Life of Charlotte Brontë, Elizabeth Gaskell describes the dynamic of the sisters’ relationship with one of the family’s dog—a bull-dog that Emily considered her own close friend. Interestingly, this marks a first breach in the common protocol of Victorian dogs as members of the family; when one recalls that not all animals (even within species) were considered appropriate to be treated as pets, one might raise an eyebrow at the attachment between a young girl and a bull-dog (rather than a breed like a spaniel, which might have been considered more “feminine” or domestic [Surridge 6]). One sees this oddity repeated rather than reconciled in Brontë’s preservation of the bull-dog in Wuthering Heights; Brontë could have chosen to tie Catherine to the lap-dog already in the Grange, but instead Skulker, the outdoor dog, is allowed to be her companion. This odd relationship between girl and beast (as opposed to pet) has deeper implications, again throwing directly back to Brontë’s actual relationships with animals. Gaskell describes in detail a scene that once again forces scholars to reassess Emily Brontë as an “animal lover” in the traditional sense. When Keeper would misbehave, Emily apparently took it upon herself to put the dog in its place:

“Down-stairs came Emily, dragging after her the unwilling Keeper, his hind legs set in a heavy attitude of resistance, held by the ‘scruff of his neck,’ but growling low and savagely all the time. The watchers would fain have spoken, but durst not, for fear of taking off Emily’s attention, and causing her to avert her head for a moment from the enraged brute. She let him go, planted in a dark corner at the bottom of the stairs; no time was there to fetch stick or rod, for fear of the strangling clutch at her throat—her bare clenched fist struck against his red fierce eyes, before he had time to make his spring, and, in the language of the turf, she ‘punished him’ till his eyes were swelled up, and the half-blind, stupefied beast was led to his accustomed lair, to have his swollen head fomented and cared for by the very Emily herself (Gaskell 309-310).

Here Gaskell shows us a disturbing picture of Emily Brontë’s embodiment of brutal love—a brutality that echoes observations of Heathcliff’s inability or unwillingness to divorce aggression from amorous passions. The scene also recalls our attention to the inherent hierarchy of judgment invoked by the scene of cruelty; one is intensely aware that the “watchers”—our narrators—moved neither to actively protect their sister nor to intervene on Keeper’s behalf. Gaskell comments explicitly on the nature of the Brontë sisters’ love of animals:

“The feeling, which in Charlotte partook of something of the nature of affection, was, with Emily, more of a passion. Some one speaking of her to me, in a careless kind of strength of expression, said, ‘she never showed regard to any human creature; all her love was reserved for animals.’ The helplessness of an animal was its passport to Charlotte’s heart; the fierce, wild, intractability of its nature was what recommended it to Emily” (Gaskell 308).

Emily Brontë’s behavior toward Keeper shows that the young woman was, in spite of her documented love for animals and the sympathy narratives some of her writing may invoke, capable of asserting her human prerogative of power over an animal inferior who had violated higher-order rules. In Wuthering Heights, Emily Brontë’s animal narratives may seem to enact structures of sympathy that align with notions of feminism, but only to a certain extent. Rather than glorifying the victim, condemning insult of speech or act, or banishing cruelty, Brontë seems to be proposing a rethinking of rights within what Derrida called a structure of “carnivorous virility” (Kreilkamp 93). It could be surmised that of Kreilkamp’s carnophallocentrism, Brontë’s clearest point of departure from a status quo that engages inequality, comes not in the exercise of cruelty, but rather in the fact that the right to wield phallic power is limited to the male sex.

Emily Brontë’s context was that of a religious patriarchy with strong social controls and strict expectations of women. Wuthering Heights becomes more accessible to feminist readings if one views Emily Brontë’s very act of writing and publishing as the foundation of a lexicon of protest. By adopting a gender-neutral pen name (Ellis Bell) and producing work in spite of societal discrimination against women working as novelists, Emily Brontë adopted the language of her oppressors and empowered her own voice. Even if Wuthering Heights is not a piece of feminist literature per se—and I would argue that it is not—it does through its success represent what Montefiore calls “female literature”: literature by women that relates stories of women, fictional or otherwise (70-71). I argue that Wuthering Heights cannot be a strictly feminist text given its tendency to attempt to resolve in favor of accepted marriage conventions and the persistent efforts of its (albeit unreliable) Ellen Dean to speak for common virtue. However, if one follows Kennard’s lead in parsing the characters of Wuthering Heights not exclusively as representatives of types of people that stand judgment but rather as conflicting elements of self, Nelly may be that part of Emily Brontë that follows society’s mandates in spite of any ensuing discontent. Nelly could be the force that allows Emily Brontë to forego credit for her work, recognizing the limitations of even the most empowered female voice. And yet for all her flaws, Nelly cannot help but recognize the truth of Catherine’s love for Heathcliff and the problematic insincerity of Catherine’s union with Edgar Linton, even as she follows the obvious social mandates in supporting and celebrating the marriage. In recognizing that Brontë spares the often antagonistic Nelly Dean the full judgment of hypocrisy she demands for the Belgian gentlewoman blind to her “angel”-child’s abuse of a helpless butterfly, one begins to understand Dean beyond the oversimplified notion of the stock character of social propriety.

To further explore the reading of Wuthering Heights as a precursor to feminist texts of appropriation or reclamation, one must pay keen attentions to the manner in which Brontë thrusts her unique experience of strength and femininity into a story functioning in her real status quo. Abraham notes that as a regime—an organization that works through rules—patriarchy as a gendered organization necessarily functions according to gender rules (93). In “Heretic but Faithful: The Reclamation of the Body as Sacred in Christian Feminist Theology” Annalet van Schalkwyk reinforces the link between patriarchy, misogyny, and fear; female sexuality was met with aversion because unless objectified the woman could threaten power structures (138). According to van Schalkwyk, “…this patriarchal system of power over the bodies of women converged with other hierarchical forms of abuse of bodies—whether it was ‘native’ and black people’s bodies, or the earth as a living community of organic bodies” (138). It is important to remember that despite the clear link between religion and patriarchy, Emily Brontë remained firmly devout. Religious doctrine directly informed the suppression of the Victorian female on all levels; religion reinforced male dominance, demanded female purity, threatened blasphemous behavior with punishment in the hereafter, and more. Brontë need not have identified as homosexual (after Kennard’s theory) to suffer from a crisis between faith and femininity; what little we know of Emily Brontë is enough to suggest that she was by no means the portrait of the ideal Victorian woman. Peppered throughout Gaskell’s Life of Charlotte Brontë are descriptions of Emily that detail her in terms of her otherness: Emily is taller and larger than her sisters, she is reserved (as opposed to shy) (135) with a “countenance…full of power” (147), she has “cropped hair” (147), and she wanders the moors rapturously. According to Gaskell, “Liberty was the breath of Emily’s nostrils; without it she perished” (149). The wildness and liberty here—qualities that patriarchal society rule impermissible in women—are not apologized for in Wuthering Heights or any of Brontë’s other writing. On the contrary, the firmest link between rights literature and the exposition of Brontë’s villains comes in the abusive quality of holding any creature captive. Throughout the story of Wuthering Heights power plays emerge wherein one character asserts him or herself by holding another hostage. Often, this act coincides with the forceful relegation of an individual to an undesirable status: Isabella wants the young Heathcliff locked in the cellar, thus rendering him a beast; Heathcliff holds Cathy prisoner at Wuthering Heights to force her to become Linton’s wife (Crouse 181-183). On a more abstract note, Catherine Earnshaw’s marriage to Edgar Linton—undesirable despite her complicity—becomes in and of itself a confinement; in contrast to the liberation that defined her love for Heathcliff, the propriety of Catherine’s marriage to Edgar Linton and the fetters of motherhood become, literally, more than she can bear.

Wuthering Heights pits passion against reason and civilization against nature. Despite the fact that the marriage of Cathy and Hareton superficially “rights” the social order and ostensibly hints at progress toward the civilization of Thrushcross Grange, the message of the work as a whole is not clear cut. The strength of passion that contemporary critics found impermissible has become the peculiarity that continues to intrigue readers to this day. Emily Brontë succeeds almost too well in forcing the reader to mix love and hate and to accept characters as flawed. The uncomfortable situations presented in Wuthering Heights eclipse the comfortable, controlled arena of judgment that allows readers to excuse themselves by sympathizing with clean-cut heroes and heroines. Wuthering Heights so thoroughly questions life’s hierarchies that the avid reader must, in talking in Brontë’s words, question herself.

In Bitch, Beverly Gross writes, “I offer as a preliminary conclusion that bitch means to men whatever they find threatening in a woman and it means to women whatever they particularly dislike about themselves” (Gross 148). Recently, however, the word “bitch” has been “reclaimed” by certain feminist groups who recognize the complex implications of the insult. Those who would appropriate this vocabulary understand that the speaker, context, and target of the appellation all combine to produce subtly different meanings. This phenomenon can be illustrated by a simple perusal of the characters of Wuthering Heights: Catherine Earnshaw, in her brazen love for Heathcliff and lack of sympathy for even him, was a bitch in the traditional sense. Linton Heathcliff’s constant wheedling complaints—his exaggerated portrayal of all that is weak in the stereotypically feminine—could certainly be described accurately (if indelicately) as a tendency “to bitch.” Even Nelly Dean is not exempt from the “b-word”—if a “bitch” is a manipulative woman, for all her social propriety and good intentions, no one fits the bill better than Nelly Dean. And yet if one accepts the most pervasive definition of the term “bitch” as a term employed by men to berate those qualities they fear in women—qualities that might lead a woman to act in brazen self-possession of her body, neglecting her gender roles for the sake of expression, and empowering herself to rewrite life on her own terms—it seems that Emily Brontë is indeed the most glorious bitch of them all.

Works Cited

Abraham, Andrew. “Emily Brontë’s Gendered Response To Law And Patriarchy.” Bronte Studies 29.2 (2004): 93-103. Academic Search Complete. Web. 16 Dec. 2012.

Adams, Maureen B. “Emily Brontë And Dogs: Transformation Within The Human-Dog Bond.” Society & Animals 8.2 (2000): 167-181. Academic Search Complete. Web. 13 Dec. 2012.

“bitch, n.1”. OED Online. December 2012. Oxford University Press. 14 December 2012 <http://www.oed.com.queens.ezproxy.cuny.edu:2048/view/Entry/19524?rskey=PQiNuY&result=1>.

Boddice, Rob. “Manliness And The “Morality Of Field Sports”: E. A. Freeman And Anthony Trollope, 1869-71.” Historian 70.1 (2008): 1-29. Humanities Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 13 Dec. 2012.

Brontë, Emily. Wuthering Heights. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009.

Brown, Kate E. and Kushner, Howard I. “Eruptive Voices: Coprolalia, Malediction, and the Poetics of Cursing.” New Literary History 32.3 (2001): 537-562. Project MUSE. Web. 13 Dec. 2012. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>. Caesar, Judith. “Brontë’s “Wuthering Heights”.” Explicator 63.3 (2005): 149-151. Humanities Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 13 Dec. 2012.

Crouse, Jamie S. “’This Shattered Prison’: Confinement, Control, and Gender in Wuthering Heights. Brontë Studies, 33 (Nov., 2008): 179-191. Web. 16 Dec. 2012.

Flegel, Monica. ““How Does Your Collar Suit Me?”: The Human Animal In The Rspca’s Animal World And Band Of Mercy.” Victorian Literature & Culture 40.1 (2012): 247-262. Humanities Source. Web. 13 Dec. 2012.

Flynn, Charles P. “Sexuality and Insult Behavior.” The Journal of Sex Research, 12.1 (Feb., 1976), pp. 1-13. Web. 13 Dec. 2012.

Gaskell, Elizabeth C. The life of Charlotte Brontë. Vol. I. 2nd ed. London: Smith, Elder, And Co., 1857. E-book.

Grose, Francis. A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue. London: S. Hooper, 1785. E-book.

Gross, Beverly. “Bitch.” Salmagundi 103 (1994): pp. 146-50. Web. 13 Dec. 2012.

Kreilkamp, Ivan. “Petted Things: “Wuthering Heights” And The Animal.” Yale Journal Of Criticism 18.1 (2005): 87-110. Humanities Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 13 Dec. 2012.

Montefiore, Janet. “Feminist Identity and the Poetic Tradition.” Feminist Review 13 (Spring, 1983): 69-84. JSTOR. Web. 16 Dec. 2012.

Ritvo, Harriet. “Our Animal Cousins.” Differences 15.1 (2004): 48-68. Humanities Full Text (H.W. Wilson). Web. 13 Dec. 2012.

Ritvo, Harriet. “Science As Literature, Science As Text.” Journal Of Victorian Culture (Edinburgh University Press) 5.1 (2000): 136. Academic Search Complete. Web. 13 Dec. 2012.

van Schalkwyk, Annalet. “Heretic But Faithful: The Reclamation Of The Body As Sacred In Christian Feminist Theology.” Religion & Theology 9.1/2 (2002): 135. Academic Search Complete. Web. 16 Dec. 2012.

Scanlon, Jennifer. “Sexy From The Start: Anticipatory Elements Of Second Wave Feminism.” Women’s Studies 38.2 (2009): 127-150. Humanities Source. Web. 16 Dec. 2012.

Surridge, Lisa. “Dogs’/Bodies, Women’s Bodies: Wives as Pets in Mid-Nineteenth Century Narratives of Domestic Violence. Victorian Review , 20.1 (Summer 1994): 1-34. JSTOR. Web. 16 Dec. 2012.